September 14, 2020

Last Friday, the materials for our new roof were delivered. Tiles, ridge tiles, clips, battens, everything the roofers would need to start the job the following day.

Except, I spotted, the membrane that goes between joists and tiles. Without that the job couldn’t even start. To be honest, we’re relaxed about the schedule, but I knew our building company prides itself on being ahead, rather than behind, and our choice of tiles had taken time to source, so they were only just ‘on track’.

I could see the delivery driver had a pallet-load of it on his truck, so I asked the question, just in case. It wasn’t on his delivery sheet, so he called the office. They didn’t have it in the order either.

“Well I’ve got a pallet load here, so I’ll take a roll off and we can sort out the order with our client back in the office. That saves me coming back later if it is missing.”

When I told our project manager, she said that’s why they always use that building supply company, because they focus first on foremost on taking care of their clients and end-users, rather than sticking rigidly to procedure.

I’d interfered in the process wrongly, as it happened. The membrane wasn’t missing. When the roofers turned up next day, they brought a big roll of it with them, and put it back in their van once they saw it wasn’t needed.

Obviously what was really missing was a clear understanding of who’s responsible for what, apart from inside the project manager’s head. Does it always work this way? Or does that depend on the roofer? If everyone (including the client?) knows it’s always the supplier’s job to supply everything, this sort of mix-up wouldn’t happen.

What could remedy that? A Customer Experience Score.

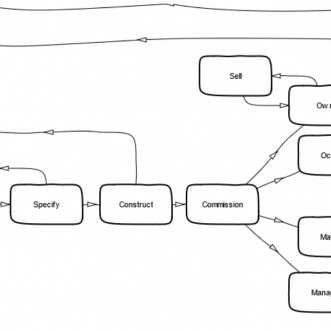

Not a procedures manual to consult every five minutes and follow slavishly. Rather, a high-level picture of ‘what happens when’ that can be quickly and easily learnt by each new person or business that comes on board. Something that says “This is how we do things, so if you join us, you need to understand this too”. That way everyone is empowered to make sure things happen as they should, even if they don’t actually work for you.

In this case the mix-up happened the right way round. The roofers finished at 10pm on Sunday, having worked their socks off for two days. Our build is back on schedule, and I’m happy to recommend our building company to anyone.

But I’m also going to suggest a little composition.