Not freedom or order, but freedom and order.

This is the second post inspired by an extract from ‘Leadership and The New Science’ by Margaret Wheatley, entitled “Change, Stability, and Renewal: The Paradoxes of Self-Organising Systems“

To recap: if a business has a strong frame of reference in place – its Promise of Value and its ‘way we do things round here’ – then it can be confident that any changes that occur will be consistent with that frame of reference.

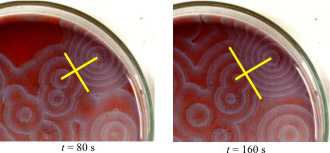

This means that not only a business can afford to be open to small variations (what Holacracy calls ‘tensions’), it needs to be – especially to small, persistent variations that are driven by the people it serves – its customers.

This in turn means that it makes sense to give people full autonomy to respond to variation, because you know they will do so in line with the Promise of Value at the core of the business, so no harm will be done, and because what starts as a small variation may well turn into a new opportunity, a new product or service, a new way of doing things, that makes the business stronger and more stable over time.

Most of us like things to stay the same, we seek order and predictability. We fear that loosening control will lead to too much fluctuation and eventually chaos, so we tend to keep systems rigid and control centralised.

The paradox is that the opposite is what we need to maintain the identity and stability of our business over the long term.

Not freedom or order, but freedom and order.

Discipline makes daring possible.