The next step

Just because you’ve got someone over the threshold, doesn’t mean you stop guiding. The destination may be obvious to you, but is it to your client?

The next step is difficult to take if you don’t where it is, or where it leads.

Just because you’ve got someone over the threshold, doesn’t mean you stop guiding. The destination may be obvious to you, but is it to your client?

The next step is difficult to take if you don’t where it is, or where it leads.

I loved Seth Godin’s blog post yesterday.

In it he talks about the gap in customer service between one person in your team and another – or even between the same person on a good day and a bad day – and how you might address it.

One approach is to nail everything down so much that delivery of the experience is exactly the same, no matter who is giving it. Another is to leave it to a great person doing the job, giving them “room to shine. With all the variability that entails.”

“It’s almost impossible to have both.”

Almost, but not impossible.

Hire great people, give them a Promise of Value and a Customer Experience Score, that creates a floor, but no ceiling, then set them free to interpret it in their own way.

Variations on a theme. The best of both worlds.

A Promise of Value, properly articulated, is quite a comprehensive thing. As a kind of definition of your culture, it’s too big to reduce to an easily applicable ‘mission statment’. That’s why you have a Customer Experience Score – it embodies your Promise of Value in the actions your business takes on a day-to-day basis.

There are times though, when the Score can’t help, because the situation in front of you has never happened before, and could not have been foreseen. Often these times are crises, when your people don’t have the time to delve into the Promise of Value for guidance. They need something more immediate, concrete and practical, less open to interpretation.

This is where an Unbreakable Promise comes into its own. It’s another brilliant idea from Brian Chesky which I’ve incorporated into my Define Promise process.

Here’s how it works:

Once you have your Promise of Value defined, in all its expansive glory, identify who the key stakeholders for your business are. Obvious stakeholders are clients or customers, your team, your investors, your suppliers etc, but you can define as few or as many as you want.

Then for each stakeholder group, define a promise you will never break, based on what’s already in your Promise of Value.

Make that promise as concrete and measurable as you can. Someone in your team needs to be able to tell in a split second whether it is about to be broken, and the kind of action they should take to prevent that. It’s usually easier to phrase it negatively – “we will never…“, rather then positively “we will always…”, but whatever works for you.

Then make sure that all your different Unbreakable Promises are in accord with each other – that by keeping one, you don’t break another.

Finally, make sure everyone knows them off by heart.

Unbreakable Promises are not easy to make, and there’s no guarantee they won’t be broken. It’s impossible to predict every eventuality. But having them is a great way to set the boundaries of interpretation of your Customer Experience Score.

Discipline makes daring possible.

Most of the time, I model what happens in a given interaction from a single perspective – that of the organisation whose Score I’m drafting. Most of the time, that’s been OK.

But when the organisation you’re working with is actually a collection of organisations each playing different Roles, this isn’t good enough.

For example, what looks like ‘placing an order’ from one side is ‘create a consignment’ on the other. The only way to keep clear about what has to happen in order for each party to keep its Promise, is to model it in these terms.

It feels awkward and clunky, but clarity trumps elegance, every time.

Here’s a funky illustration of what I mean.

Makes me want to make one.

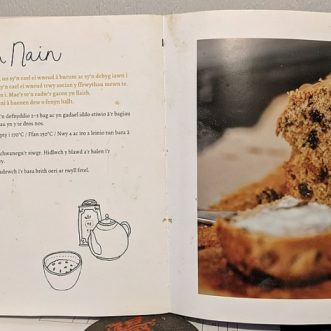

When you first write down your Customer Experience Score, it’s likely to be very like a recipe – a set of detailed, step-by-step instructions to create a very specific outcome.

That’s great. Recipes can be a great way for you to get stuff out of your head, and for people to build confidence.

But they can also become a trap that undermines confidence. If people have never learned the basic techniques and methods that underly any recipe, its easy for them to become reliant on having exactly the right ingredients, the right pots and pans, the right equipment and the right actions, in the right order…

That makes for a lot of work, a lot of shopping, a lot of planning and a lot of anxiety too, which makes cooking a joyless activity for many.

Cooking doesn’t always have to be ‘fun’, but there’s no reason why it shouldn’t be relaxed, exploratory, and sometimes, surprising. By understanding the patterns hidden in recipes, we can start to play with them, tasting and learning as we go, until eventually, we can improvise a nourishing meal out of whatever we happen to have in the kitchen.

The same is true for your Customer Experience Score – recipes can be a great start. But results will get better if you allow people to tweak and experiment and improvise a little. Just make sure to ‘taste as you go’ and things will be fine. Eventually, people won’t need the recipes, they’ll be able to improvise a great customer experience with the resources around them and the customer in front of them.

Who knows? One day, their Bara Brith will be even better than yours.

If you’d like to become an effortless cook, my friend Katerina is running a workshop next weekend.

I did this and it honestly changed my life.

If you make getting paid part of the process of delivering your service, its easier to make sure it happens, on time.

Remember though, to also make it part of the customer experience.

There’s no reason why your customer shouldn’t enjoy it too.

When you’re trying to capture your Customer Experience Score, it’s easy to get yourself bogged down in detail, trying to nail down every step of every activity to the nth degree.

You can avoid this by reminding yourself who you’re writing the process for – a competent human being, not a machine. One of the great things about humans is that you don’t need to tell them everything. They can fill in the gaps from their experience, using their skill and judgement.

So if you find yourself documenting the equivalent of ‘make a cup of tea’ in excruciating detail, you’ve gone too low. On the other hand, if everyone following your Score has to stop and ask you “What am I supposed to do here?“, you’ve stayed too high. If some of your players are too new to know already, by all means, document ‘how to make a cup of tea’. As part of their training, not part of the Score.

The only way you’ll know how near you are to the sweet spot is to do it, find out and adjust accordingly.

What should you do when an important piece of data about a customer has been ‘lost’?

You tell them its their fault of course.

You send them a letter threatening them with loss of the service unless they rectify the mistake.

And since you’ve lost the same piece of data for thousands of customers, you make sure there are no extra people to answer the phone number you’ve given them.

I wonder how many customers they’ll lose as a result?

I know I’m cynical, but could ditching clients actually be the point?

It seems a pretty good way to go about it.

It’s a well-known phenomenon. As a one-person or few-person business grows and adds more people it becomes less and less efficient. As more people are added and roles are specialised, overheads are added too – of communication, coordination and support, and eventually management.

The result is that a business spends time in what Seth Godin calls The trough of inefficiency. Perhaps even getting stuck there forever.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

When you started your business, you were its CEO – Chief Everything Officer. You did everything, gradually shaping a unique end-to-end process for making and keeping promises to the people you serve. A process that works.

We fall into the trough of inefficiency because we think of our businesses as pin-factories – a set of tiny, repetitive operations chained together, managed by someone who can see the bigger picture, who has the whole process in their head.

Why not simply replicate the Chief Everything Officer instead?

If you can do it, so can someone else. Especially if you tell them what you do.

Tell them your Promise, Tell them what you do to make it, and what you do to keep it. Write it down like music in a Customer Experience Score so that they can run the whole thing themselves, even when you’re not in the room.

If everyone’s a Chief Everything Officer, you only need meetings for business-changing decisions, not the day-to-day.

If everyone’s a Chief Everything Officer, you don’t depend on specialists. When everyone knows everything that needs doing, they can support each other.

If everyone’s a Chief Everything Officer, You don’t need managers. People co-ordinate themselves, managing their own Customer Experiences.

Even better, further growth is simple. For more impact, add more Chief Everything Officers.

A Customer Experience Score can your ladder out of the trough of inefficiency.

It works just as well as a bridge to stop you falling in in the first place.

It’s long been assumed that people find it harder to compare between high-value options than between low-value ones. To put it concretely, we’re supposed to find it harder to compare a £350,000 house and a £355,000 house, than to compare a £90,000 house and a £95,000 one.

The idea is that although the size of the difference in value might be the same in both cases, as the proportion of the difference shrinks, comparison becomes harder.

It turns out this assumption is wrong. In a recent study, researchers found that not only are we more accurate in our selections, when more value is at stake, we can also be fast. And when we are given context – in other words, we know there’s a lot at stake – we consciously slow down to make our decision better.

This has some implications for pricing. You can’t take a ‘nobody will notice the extra £xxx’ attitude. People will expect to see higher value for a higher price, and they can tell the difference.

Perhaps more interesting are the implications for delegation. We’re smarter than we thought.

You can trust your people with bigger decisions than you might have assumed. Especially if you give them the context to make them in.