June 25, 2019

Humans are very good at taking ideas or feelings that are abstract, implicit, unexpressed, and possibly inexpressible, and giving them a concrete form, so that we can reason about them as if they have a real physical presence.

We do it all the time, with maps; forms; questionnaires, diagrams; musical scores; plans; and especially software. Those familiar icons on your phone or laptop screen are reifications of the idea of a dustbin, or a filing system, just as the original dustbin was a reification of the idea of ‘a place to collect rubbish’.

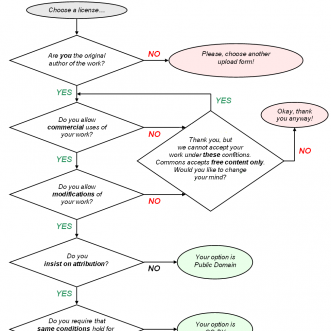

This is OK when we know that we are doing it. When we look at a map, we know it isn’t the territory. But when we give the map a voice that tells us where to go next, we forget that it is a map, and treat it as if it is real – more real than the territory.

But the most dangerous thing about this aspect of reification is that some ideas and feelings are possibly inexpressible, which means that in order to capture them, we must simplify them, reduce them, lose nuance – lose meaning.

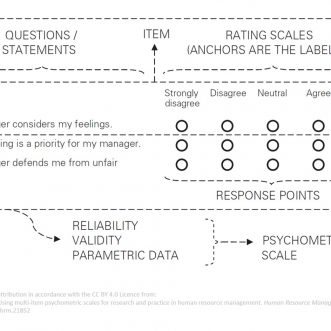

We’ve all filled in questionnaires, for serious purposes or for fun, where some of the answers don’t really fit with our experience. But we have to choose one, so we go with an answer that is the nearest, or which captures one aspect of it. By the time everyone does that, the people who formulated the questionnaire have created a model of the group of questionnaire answerers that in fact does not capture the reality at all.

That’s fine if it was just for fun, but what if that model is then used to build the ‘systems’ (not necessarily software) and institutions that surround us? It becomes the reality, and woe betide you if you don’t quite fit.

So, it’s important to be aware that the map is not the territory. The way we model the world around us is not the world, and other models are available – even if we haven’t dreamed them up yet.

And, I think, its important to leave inexpressible things unexpressed. Some parts of the score should be left to the imagination of the musician. They’re usually the most memorable parts of each performance.