June 22, 2020

The thing I love about reading, is that I’m always finding new ways of saying things, from people who can say them much better than me.

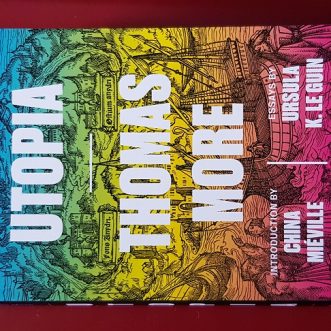

This midsummer weekend, I finally got round to reading the Verso edition of Utopia, by Thomas More. It was not More’s words that struck me, but Ursula K. Le Guin’s – in fact not always her words, but words she assembled, interpreted and discussed in the first of her essays included with this book: “A non-Euclidean View of California as a Cold place to be”.

“The activities of a machine are determined by its structure, but the relationship is reversed in organisms – organic structure is determined by it’s processes”*

“The societies which have best protected their distinctive character appear to be those concerned above all with persevering in their existence.”**

“Persevering in one’s existence is the particular quality of the organism; it is not a progress towards achievement, followed by stasis, which is the machine’s mode, but an interactive, rhythmic, and unstable process, which constitutes an end in itself.”

“Since the day of the Roman empire and the Christian church, we hardly think of a social activity except as it is coherently Organized into a definite unit definitely subdivided. But, it must be recognized that such a tendency is not an inherent and inescapable one of all civilization.”***

I (like Le Guin) found Thomas More’s Utopia unsatisfactory. It is founded on force and maintained through slavery. It’s activities are determined by its structure. It is like most utopias,“the product of ‘the euclidean mind’ (a phrase Dostoyevsky often used), which is obsessed by the idea of regulating all life by reason and bringing happiness to man whatever the cost.”****

Here’s a stab at pulling this all together into something relevant for me as Gibbs & Partners:

- Most human beings, including business owners, are simply trying to persevere in their existence.

- Most corporates, built as machines, where structure determines process, are inimical to this. Which is why people, when they get the chance, retire, or leave and set up their own small businesses, often with no idea of growth, simply as a means of persevering in their existence.

- What I’m making explicit and to an extent formalising, is an alternative, organic view of a business where process (the making and keeping of promises) determines structure. An alternative Le Guin might call yin.

- By formalising this structure, I’m trying to create a blueprint for documenting the ‘laws’ of a business that enables it to be both a place where people can persevere in their own existence and a generator of the growth, innovation and profit that will create more spaces for more people to persevere in theirs. A place where it’s possible to enjoy both freedom and happiness.

- I’m by no means the only person I know of trying to do something like this. I’m part of a trend, that recognises the need for humanity to make “a successful adaptation to their environment and learn to live without destroying each other.”****

As Derek Sivers puts it:

“When you make a business, you get to make a little universe where you control all the laws. This is your utopia”.

Welcome to mine.

*Fritjof Capra, The Turning Point (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1982). Excerpted in Science Digest (April 1982), p. 30.

**Claude Levi-Strauss, The Scope of Anthropology (London: Jonathan Cape, 1968), pp. 46-47. Also included in Structural Anthropology II (New York: Basic Books, 1976), pp. 28-30. The version here is Le Guin’s own amalgam of the two translations.

***Alfred L. Kroeber, Handbook of the Indians of California, Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin no. 78 (Washington, D.C., 1925), p. 344.

****Robert C. Elliott, The Shape of Utopia (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970)