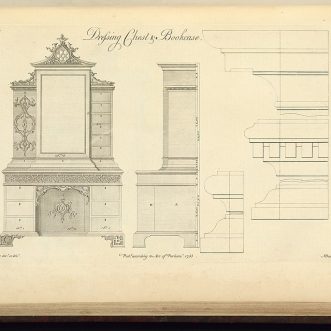

Chippendale

In the pre-industrial age, the only way to grow your business was through apprenticeships. Teaching aspiring masters everything you knew one-to-one, or one-to-few.

Once they had mastered their craft those apprentices went off and repeated the process in their own workshops. A few might stay with you if you could get enough work to employ them.

The downside for customers was that everyone tended to make the same, tried and tested stuff for the same local customers. If you wanted to make your mark by producing something different, it was impossible to grow fast enough to keep up with demand.

Thomas Chippendale knew what his gentleman customers in London wanted. He knew that there were similar markets in towns and cities across the country. He couldn’t serve those markets himself, but he could enable other cabinetmakers to do so – with a pattern book that could be sold to both cabinetmakers and gentlemen.

The pattern book specifies the end product – what it should look like, dimensions, some key details. Chippendale knew that of course any master cabinetmaker would know how to construct the pieces. He didn’t need to tell them that.

The result is that each piece produced from the pattern book reflects the skills of the cabinetmaker who used the pattern as inspiration, tailored to the sensibilities of their local gentlemen customer.

‘Chippendale’, but not by Chippendale. A halfway house between handcrafted and factory-made.

Not a bad way to scale your unique approach.