Thinking about flywheels, again.

I’ve been thinking about flywheels again.

Here’s one I drew to illustrate what I can do for a business:

A business freedom flywheel

Does that make sense to you?

Do let me know.

I’ve been thinking about flywheels again.

Here’s one I drew to illustrate what I can do for a business:

A business freedom flywheel

Does that make sense to you?

Do let me know.

I’ve only ever met one person who wanted to be a manager. Most other people want to be technicians (because that’s what they were in the company they left), and some are genuinely entrepreneurs.

So why do we have managers?

According to the e-myth, managers sit between an entrepreneur with a vision and the bunch of technicians who make the thing the business sells. Managers organise technicians to deliver the vision.

It doesn’t have to be like this. Take an orchestra. An orchestra is a bunch of technicians, delivering the vision of someone who’s usually dead. The nearest thing to a manager is the conductor, and that’s stretching it a bit. The conductor doesn’t organise, they interpret, co-ordinate, keep the tempo up.

So what makes an orchestra possible?

The score. The talent, skill and ability of the players. Lots of practice.

If you want more impact just add more players. If you want to play at more venues, assemble more orchestras. The score tells everyone what they need to know. No interface needed, no managers required.

All the extra spend goes in front of the camera, where the audience will experience it. Less overhead, more profit. In other words, scale as opposed to growth.

Since scale is what everyone looks for, modelling a business to be more like an orchestra might make a lot of technicians and entrepreneurs very happy.

A while ago, I wrote about Mintzberg’s continuum of management, which looks something like this:

I’ve been thinking, and I think it should look like this:

What do you think?

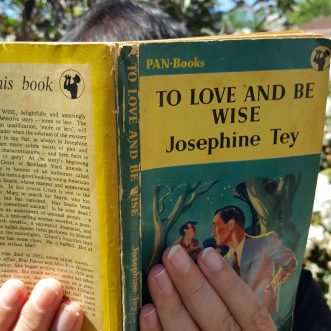

I’ve just finished reading this book, the first of 3 I ordered after hearing Margaret Heffernan on the radio last week.

It’s a worrying and challenging read, exploring and explaining just how naturally easy it is for we humans not to see what’s in right in front of our eyes.

The reasons are varied, from feelings of affinity or love, wanting to fit in or please people in authority, too rigid systems, distance and disconnection, the bystander effect, a narrow focus on money or sheer cognitive overload and exhaustion. Sometimes, in the worst scenarios, such as Grenfell Tower or Texas City, several reasons combine and exacerbate each other.

The answer is to make ourselves see better. Systematically, intentionally, but never mechanically.

We do that by encouraging diversity of thinking and argument, by thanking whistleblowers, complainers and critics instead of sidelining them.

We do it by constantly reminding ourselves of what we are in business to do – to make and keep promises to human beings, our customers, and by eliminating the hierarchies, silos and long chains of command that get in the way of that.

We do it by creating transparent ways of working that keep our promise visible and support people to hold each other accountable as human beings for seeing what’s really there, and acting on it.

And of course the irony is that if we do these things well, we will create more value and do better financially. Because its not only bad things we make ourselves wilfully blind to, its also opportunities.

We’ve all suffered from it. Corporate amnesia. You call a company you’ve done business with for years, and give them your name, address, and inside leg measurement 3 of 4 times before you get to the point of the call.

A more insidious form of corporate amnesia forces a team member to recall the process before they perform a task, instead of having the system remember it for them.

This kind of amnesia results in variation over time and between team members. Sometimes the variations will be improvements, but most often they are an ever-worsening copy of a long-forgotten original, void of life or meaning. Any improvements are forgotten, because the organisation has no way to capture them or remember them.

This isn’t just amnesia, its also akrasia – doing one thing when you should be doing another.

Because if you’re too busy remembering what’s supposed to happen, you aren’t making it happen.

I learned a lovely new word yesterday. ‘Akrasia’. It means doing one thing when you should be doing something else.

I’m guilty of that all the time, sometimes as a form of procrastination (I know I should eat my frog, but I’ll just have ice-cream first), occasionally as a form of hiding (doing the easy thing, because the hard thing is scary).

But whole companies are guilty of akrasia too. They spend time, money and attention instructing down and reporting up the management hierarchy, when they should be making and keeping promises to the people they serve instead.

The solution is simple.

Structure your business around doing, not monitoring.

If you’ve ever started up a spin bike, you know about flywheels.

They take a lot of effort to get going, but once they’re off, the energy you put in is released, making it much easier to keep momentum going for longer.

That’s a pretty good metaphor for building a system for making and keeping promises. It takes effort to get up and running, but once it is, it can keep going almost forever.

Long after you’ve jumped off the bike.

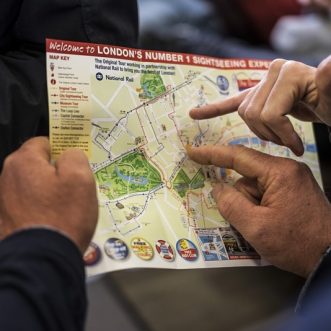

When you’re new to a place the kind of map that’s useful isn’t all that detailed. All you need is something that can tell you where you are in relation to landmarks you’ll easily find and recognise, so you can see where to head next.

This kind of ‘big picture’ never happens by accident. It’s not an aggregation of local details. It’s designed, top-down, on purpose as a guide for strangers.

If your business is your Utopia, why not make a map of it? Big picture enough to let people navigate safely by themselves, or easily enlist help from a passing stranger if they go astray.

You might find you get fewer pinch points, and less people stuck down blind alleys.

I tell you a lot about the books I read. I hope you find that interesting.

I’d also like to know what you read.

What’s your favourite book for:

I’d be really interested to know.

“The activities of a machine are determined by its structure, but the relationship is reversed in organisms – organic structure … Read More “The best of both worlds”