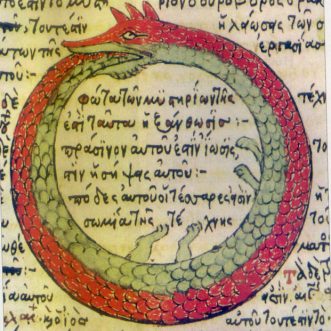

Eating your own tail

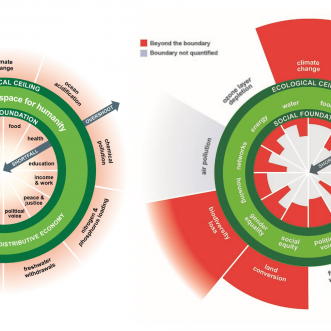

We’re used to thinking linearly – we picture our businesses and our lives as a sequence of events or processes, each of which takes an input and turns it into an output.

The trouble with this approach is that it encourages us to forget that inputs have to come from somewhere, and that outputs have to go somewhere. When we’re all working like this, we exhaust the larger system we are part of.

The answer is to find ways to eat your own tail.

Could you re-use the output from one of your processes as an input to another? A few years ago I met a tomato grower. They maximise the sunlight on their tomatoes by stripping off most of the leaves. The leaves power an anaerobic digester. The digester produces methane that is burned to generate electricity to heat the greenhouses. Carbon dioxide from the engine is also fed into the greenhouses to help the tomatoes grow faster.

The result is an almost closed, circular system.

Could you find ways to eat your own tail in your business?

If not, the answer might be to get a few businesses together and eat each other’s tails instead.

One business’s waste product is another business’s vital input. A data centre’s excess heat could keep nearby homes or facilities warm, or refrigerate a food store. A restaurant’s cardboard could become a horse’s bedding, could become a market gardener’s compost, could become a restaurant’s vegetables…

Whose tail could you bite? Who could usefully bite yours? How could you make your business and it’s environment circular?

The thing about circles is they never end. They just keep rolling along.

Today’s post is inspired by Vittles newsletter. I recommend it.

-crd-331x331.jpg)