May 24, 2023

This junction, near where I live, used to be managed by traffic lights. It’s a busy junction on the relief road around the town centre. It’s used by cars crossing through the town in 4 directions, buses getting into the town centre, and pedestrians heading to the shops or to catch a bus.

With traffic lights, everyone had equal priority. Queues of cars and buses would build up, while each lane took it’s turn. Pedestrians would wait for 5 minutes or so to get their turn. At rush hour, the car queues would back up a long way, making everyone grumpy and selfish, blocking the junction for everyone.

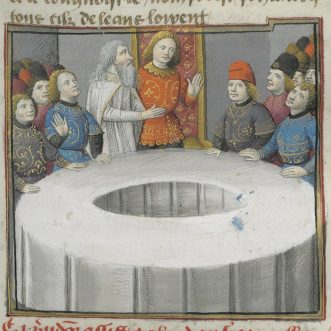

Then, several years ago, it was turned into this roundabout.

A roundabout is a pretty wonderful invention. It’s not really a thing, but a protocol, a set of rules based on responsible autonomy. A driver chooses when to use it, responsible not just for their own safety, but also the safety of other users. Busy roundabouts aren’t always great through, the entrance with the heaviest traffic ends up having a de-facto higher priority than the others, and at busy times, pedestrians barely get a look in.

For the best possible flow of traffic, the answer was to make the roundabout part of a shared space like this, where pedestrian crossing places (but not zebra crossings, which would give pedestrians priority) are clearly marked, and the painted roundabout gives drivers a clue how to use it, but not the priority a built-up roundabout with signage would give them over pedestrians.

The roundabout protocol governs the cars at busy times, and the uncertainty of the pedestrian crossings means at all times, everyone has to slow down, look at their fellow road users and negotiate their way across the space.

The difference this made was immediate and huge. It’s busy at rush hours, and that makes drivers a little less likely to stop for pedestrians, but its never been as bad as it was before.

But what I only realised the other week, when I took this photo, was that in this space, the pedestrians make the roundabout work even better.

A pedestrian crossing one arm of the junction can break a flow of car traffic and give cars on another arm a chance to get on the roundabout. So even at busy times, traffic flows more or less smoothly, because when there are more cars, there are also more pedestrians to interrupt the flow.

The best thing of all though, is that this setup enables people to see each other as people – we make eye contact, acknowledge each others’ presence and most of the time behave graciously towards each other.

It’s a self-managing system, with people at its heart.

What’s the relevance of this to a small business?

Well, a founder usually starts off as a set of traffic lights, controlling everything strictly from the centre.

When this gets too much, they might delegate the traffic lights job to a manager, a ‘traffic cop’. Which isn’t much fun for the traffic cop and doesn’t change anything for road users.

Or they install policies, rules, procedures, expecting people to follow them with the same level of strictness. Which makes things better, but still not as flexible as they could be, and certainly not as much fun. Things still get clogged up at busy times, and pedestrians (the people) often get ignored.

My answer is to put a system like this into place:

Install a protocol based on responsible autonomy (a Customer Experience Score), into a shared space of values (your Promise of Value), that’s focused on the desired outcome (Making and Keeping your Promise to customers) and gives plenty of room for gracious flexibility. To create a self-managing system, with people at its heart. No supervision required.

Discipline makes Daring possible. But only when the Discipline isn’t rigid.

Ask me how.