Over to you

This is my 473rd blog post.

Thank you for receiving them all (so far).

To celebrate I’d like to ask you something.

What would you like me to write more about?

This is my 473rd blog post.

Thank you for receiving them all (so far).

To celebrate I’d like to ask you something.

What would you like me to write more about?

How do you start building an archive and library of ordinary peoples’ diaries? By taking in one box of diaries.

How do you start a hot-air balloon festival? By getting two hot-air balloons together.

How do you start a sail-cargo business? With one hold of cargo.

How do you start writing your Customer Experience Score? By writing down one business process.

By starting. Small. By not worrying about what will be needed to make the big thing a success. Most of all, by moving from “Someone really ought to do something about this.” to “I’d better do something about this.”

Once you start, other people will join in.

Hat tip to Irving Finkel for inspiring this one.

Axioms are the foundations of ‘grammars’. They are the givens, things we don’t have to question, that we can take for granted, that are (at least to us) self-evident. Otherwise it would be nigh-on impossible to get anything done. Imagine a whole orchestra having to agree what ‘C’ means before they start playing, or having to define exactly what you mean by a ‘metre’ on every page of a set of building drawings.

For a business it’s different. Remember, “When you make a business, you get to make a little universe where you control all the laws. This is your utopia”(Derek Sivers).

That means you define your own business axioms – how many times it’s acceptable to let the phone ring before you answer it, who is most important, the boss or the customer, how much it’s legitimate to care about the environment in relation to how your busines makes money.

If the grammar of your business can be written down as what I call a Customer Experience Score, the axioms that govern what that score looks, sounds and feels like are what I call your Promise of Value.

Both are unique to your business. Together, explicit or otherwise, they are the reason your best clients buy from you, stay loyal to you, and tell their friends about you. Both are worth writing down.

My friend Julian Donnelly recommended this book to me. I’m very glad he did.

I recommend it. Don’t be fooled by the action-hero cover, what kept going through my head as I was reading it was ‘This is Dale Carnegie. This is all about empathy, and understanding motivation.”

If you’ve ever done a Dale Carnegie ‘Winning with Relationship Selling” course, you’ll recognise a lot in this book, but you’ll see it from a new angle. If you haven’t yet, this is great preparation.

It turns out that yesterday’s AWOL veg box wasn’t down to a new driver, but to a problem with the navigation software.

The driver did a great job of sorting things out. He bought a new phone, double-checked his route and corrected the mistakes. He took responsibility and did what needed to be done to really keep us happy.

Meanwhile head office was offering refunds.

Technology is brilliant, but you need a systematic way of identifying when it’s broken, as quickly as possible. Analogue visual indicators work well for this e.g.the address label on the box, a line marked on a bottle that used every day.

You also need a fall-back manual process for when the software breaks. That way, things may take a little longer, but nobody is taken by surprise, and nobody is let down. And you don’t have to compensate unnecessarily.

Do you check your phones are working every morning? Do you have backup phones? Do you keep an up-to-date back-up (maybe even hard copy) of your contacts? Do you have a process for learning from mistakes and accidents?

I’d be surprised if you do.

My veg box supplier has been growing really fast. I’m not suprised, it’s a great scheme.

Today’s veg box has gone AWOL. It’s been delivered to someone else by mistake.

I’d bet an artichoke that there’s a new driver.

And no Customer Experience Score.

Last Friday, the materials for our new roof were delivered. Tiles, ridge tiles, clips, battens, everything the roofers would need to start the job the following day.

Except, I spotted, the membrane that goes between joists and tiles. Without that the job couldn’t even start. To be honest, we’re relaxed about the schedule, but I knew our building company prides itself on being ahead, rather than behind, and our choice of tiles had taken time to source, so they were only just ‘on track’.

I could see the delivery driver had a pallet-load of it on his truck, so I asked the question, just in case. It wasn’t on his delivery sheet, so he called the office. They didn’t have it in the order either.

“Well I’ve got a pallet load here, so I’ll take a roll off and we can sort out the order with our client back in the office. That saves me coming back later if it is missing.”

When I told our project manager, she said that’s why they always use that building supply company, because they focus first on foremost on taking care of their clients and end-users, rather than sticking rigidly to procedure.

I’d interfered in the process wrongly, as it happened. The membrane wasn’t missing. When the roofers turned up next day, they brought a big roll of it with them, and put it back in their van once they saw it wasn’t needed.

Obviously what was really missing was a clear understanding of who’s responsible for what, apart from inside the project manager’s head. Does it always work this way? Or does that depend on the roofer? If everyone (including the client?) knows it’s always the supplier’s job to supply everything, this sort of mix-up wouldn’t happen.

What could remedy that? A Customer Experience Score.

Not a procedures manual to consult every five minutes and follow slavishly. Rather, a high-level picture of ‘what happens when’ that can be quickly and easily learnt by each new person or business that comes on board. Something that says “This is how we do things, so if you join us, you need to understand this too”. That way everyone is empowered to make sure things happen as they should, even if they don’t actually work for you.

In this case the mix-up happened the right way round. The roofers finished at 10pm on Sunday, having worked their socks off for two days. Our build is back on schedule, and I’m happy to recommend our building company to anyone.

But I’m also going to suggest a little composition.

My mother, who’d been taught housework by a female version of Felix Ungar out of ‘The Odd Couple‘ (a regime that soon collapsed in the face of 7 Oscar Madison-like children), loved to collect books about ‘women’s work’. Perhaps to see how the men who usually wrote them imagined these things should be done.

Two of these books stick in my memory. One was ‘The Mechanical Baby’, a history of childcare from ancient times onwards, I don’t remember the title of the other, but it might have been simply, ‘Housework’.

The housework one sticks because in it, the author applied all sorts of efficiency measures, taken from the workplace. For example, he suggested replacing the big Spring Clean, with an Autumn Clean. After all, Summer is when we fling windows open and let in all the dust, debris and insects from the garden. It’s also when all the spiders build their cobwebs in various corners of the house, so that by September, it looks like we’ve left up last year’s fake snow from Christmas. Or is that just my house?

Anyway, I think he had a really good point, but I’d recommend both, and go for Equinoctial Cleans, one as Winter turns to Spring, and the other as Summer turns to Autumn. Spring for de-cluttering, opening up and airing everything, Autumn for cleaning down, tidying away and mending, ready for the long haul of Winter. Both are a kind of fresh start, but with a slightly different emphasis.

Of course, both can apply to business too.

What’s the plan for your business Autumn Clean?

When we learn effectively we learn in stages. First we learn the rules. Then we interrogate and question ‘the rules’ to arrive at an interpretation that is meaningful for us. Finally we apply our interpretation of the rules to performance, at which point we find out if whether we have been able to communicate that meaning to our audience.

In the olden days these three stages were called Grammar, Dialectic and Rhetoric, collectively known as the Trivium, ‘the three’.

‘Trivial’ originally meant simply belonging to these three. It took on the meaning of ‘lesser’, ‘not serious’, ‘unimportant’ in contrast to its big brothers, the Quadrivium – the four other liberal arts of Astronomy Mathematics, Geometry and Music – the arts that could be said to provide ‘the facts’ behind ‘the rules’.

Of course these pursuits are not at all trivial. They are essential for effective performance. They all have to happen. Blindly accepting rules stifles creativity and progress. Questioning needs to lead to action, otherwise what’s the point? Action needs to be meaningful, not just for the individual but also for the audience, the community.

They also have to happen in the right order. It makes no sense to dive into performance without knowing what you are trying to communicate through that performance. It makes no sense to question before you know what the rules are supposed to be – you end up questioning everything, which makes any kind of performance almost impossible.

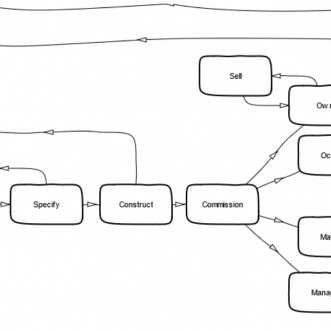

We know this, even though we no longer formally learn it. We see the trivial arts in operation all around us, whenever people undertake a creative endeavour, especially a collaborative one, such as putting on a play or concert, making a film, staging a ballet, creating a video game or putting up a building.

A business is another collaborative creative endeavour, that seeks to create profitable, repeat performances that delight and expand its audience. The problem for us business owners is that we have no tradition of looking at them in this way, which leads to some common problems:

It seems to me that one solution is to learn something from the other creative endeavours we know, where the ancient trivial pursuits of Grammar, Dialectic and Rhetoric are alive and well, even if we call them something different.

So, if you had to imagine your business was some other kind of creative, collaborative production, what would it be?

“The product you make is not your website, it’s not the travel, its not even the delightful experiences, the product is the organisation that brings stakeholders together to produce those outcomes.” Eric Reis to Airbnb’s Brian Chesky.

“In a humanocracy, the organization is the instrument – it’s the vehicle human beings use to better their lives and the lives of those they serve.” Gary Hamel and Michele Zanini in “Humanocracy”.

If all organisations are instruments, tools for making and shaping people and things, you have to ask:

“What kind of things does my business shape?” and “What kind of people does my business make?”.

The answer might seem obvious, but I’m not sure the obvious answer is always the ‘real’ one. Especially for business-to-business firms and professional services. The ‘real’ answer for you will be driven by your view of the world, but I think it’s worth exploring, because it opens up a different way of thinking about what a business is for.

For example, does an accounting practice make sets of accounts? Or does it make businesses? And in the process, does it help shape the people who work for it and with it?

I don’t know, but I can help you find out.