Cui bono?

There’s a question worth asking whenever someone says “that doesn’t work” or “we can’t do that”, or “that’s not worth investigating”.

“Who benefits from the way things are right now?”

Those are the people you really need to convince.

There’s a question worth asking whenever someone says “that doesn’t work” or “we can’t do that”, or “that’s not worth investigating”.

“Who benefits from the way things are right now?”

Those are the people you really need to convince.

When you’re setting up a client in your systems for the first time, it’s tempting to ask up front for everything you will need for the journey.

Resist.

If your tailor is making you an overcoat, you don’t expect them to measure your inside leg.

Only ask for what you need right now, to get the client started. Otherwise you’ll overwhelm them with unexpected (and to them, unnecessary, perhaps even unnerving) work, to get information that may well have changed by the time you actually need it.

Keep your information gathering aligned with what you’re doing together. That keeps it feeling natural, and you’ll have all the right information when you need it – just in time.

I used to think that the first step in Keeping your Promise was setting up the client – getting everything in place to be able to deliver your service to them smoothly and efficiently.

How very functional of me.

Now I feel differently.

Sure, your client has enrolled with you on their journey, but they are probably already feeling a little buyer’s remorse, questioning whether this really is the right thing for them. What they need now is the reassurance that you will continue to ‘see’ them as a human being, not just as a ‘thing’ to be processed.

So, start your Keep Promise with a welcome. Get the metaphorical bunting out. Find a way to make your new client feel safe, special, and seen.

It doesn’t have to be over the top. It doesn’t have to be expensive. It doesn’t have to be the same for everyone. It does need to be congruent with your Promise of Value.

How could you show new clients they are welcome?

Listening to ‘In our time’ this morning, I heard that one of the reasons our ancestor Homo Erectus emerged could be that the Rift Valley environment around them started to change relatively rapidly and unpredictably as a result of volcanic activity.

This created a new evolutionary ‘niche’ – for a species that was able to efficiently switch between environments rather than adapt efficiently to just one. Walking upright, sociality and speech are just some of the outcomes.

In other words, we’ve evolved to live in the midst of change.

To be sure, most of us prefer our change to be evolutionary rather than sudden and drastic, but I bet there’s hardly anyone you know that hasn’t undergone some sort of major shift (changed job, changed marital or parental status, moved house) in the last five years. We are programmed to explore possibilities, see opportunities, to talk about new things, to try them out – with others if we can.

Why then do corporates have such a problem with change management?

Because we’re human. We love change but we prefer to do it ourselves, than have it done to us.

The world is running out of phosphorus, a major component of fertiliser. We humans mine it, spread it on our fields, and then allow it to leach out of the soil into rivers and then oceans, where it remains, lost to us.

We can’t synthesise it artificially, so once the mines run out, that’s it. In our zeal for increasing the ‘profitability’ of our farming systems, we’ve reduced the system to its bare bones, and sacrificed it’s sustainability.

It doesn’t have to be like this. It turns out there is a way of capturing phosphorus before it becomes lost to us.

It’s called wildlife.

As we find so often, we live inside carefully balanced, complex systems, and those things we thought were pests, unnecessary, or nice to haves turn out to be crucial.

What makes ecosystems stable is richness – their complexity, multiplicity and variety. That means that wherever we humans seek to create new systems of our own, from cities to small businesses, we should look to enrich what surrounds us.

It’s our best insurance policy, and the surest route to profit. Just not the quickest.

What do your people really want?

The same things you do:

If you escaped corporate life to set up on your own, you’ve almost certainly found that having these things at work didn’t just make you happier, it made your work better too.

Pass it on. It will be worth it.

A complex evolving system, such as a planet, an ecosystem or a business, learns through feedback.

That means at least 4 things:

There has to be room within the ‘normal process’ for variation.

There has to be a way of recognising repeated variations that should be part of the normal process.

There has to be a way of quickly and easily capturing these into the new ‘normal process’.

There has to be enough ‘slack’/redundancy in the whole system to make the first 3 possible and practical.

Without these, a system fossilises, becomes irrelevant and ultimately dies.

Thanks to Seth Godin for the prompt.

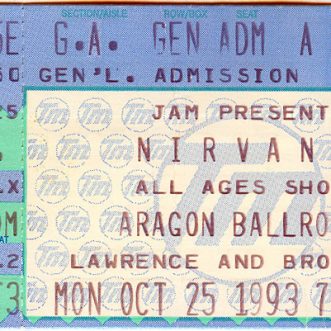

In this letter to Nirvana, pitching to produce their next album, Steve Albini sets out his Promise of Value for them to take or leave.

It’s not 100% applicable to a business like yours, (unless your business is actually a band) but there’s a lot that could be learned from it:

“I’m only interested in working on records that legitimately reflect the band’s own perception of their music and existence. If you will commit yourselves to that as a tenet of the recording methodology, then I will bust my ass for you. I’ll work circles around you. I’ll rap your head with a ratchet…”

“If the record takes a long time, and everyone gets bummed and scrutinizes every step, then the recordings bear little resemblance to the live band, and the end result is seldom flattering.”

“I consider the band the most important thing, as the creative entity that spawned both the band’s personality and style and as the social entity that exists 24 hours out of each day. I do not consider it my place to tell you what to do or how to play.”

“I like to leave room for accidents or chaos. Making a seamless record, where every note and syllable is in place and every bass drum is identical, is no trick. Any idiot with the patience and the budget to allow such foolishness can do it. I prefer to work on records that aspire to greater things, like originality, personality and enthusiasm.”

As the founder of your business, you’re the equivalent of Nirvana. You’re the live band. The customer experience you’ve carefully crafted as you grew your business is what your audience buys.

Your team, is like the records you make to get the music to more of those who want to hear it – far into the future.

Only now you are Steve Albini, and it’s your job to make sure the record delivers as if it was you:

“If every element of the music and dynamics of a band is controlled by click tracks, computers, automated mixes, gates, samplers and sequencers, then the record may not be incompetent, but it certainly won’t be exceptional. It will also bear very little relationship to the live band, which is what all this hooey is supposed to be about.”

Write your people a score, make sure they’re familiar with your sound and ethos, then let them play as human beings, not machines.

I’ve just caught the last half of ‘Life Changing’ on BBC Radio 4.

It’s a thrilling and hopefully infrequent illustration of why hierarchy sucks and free-playing, experimental and autonomously responsible human beings are the best.

After their cruise ship was holed, the captain hid and the senior managers ran away.

The entertainers worked out something was wrong, then, worried about the customers and the rest of the crew, did something about it. They initiated processes that saved all 581 people left on board, including themselves.

Maybe they were able to do that precisely because they weren’t on the org chart?

All capitalism wants is a money-machine.

Machines aren’t good places for humans (or anything that truly lives) to thrive.

One of them has to give.