Seeing ourselves

We humans are used to thinking of ourselves as self-aware, or self-conscious.

Except that most of the time we aren’t. We work on auto-pilot, following our habitual paths, working through habitual behaviours without consciously reflecting at all.

We do have moments of conscious awareness – when we’re thinking, or working out a problem – but these really are moments. 7 seconds on average.

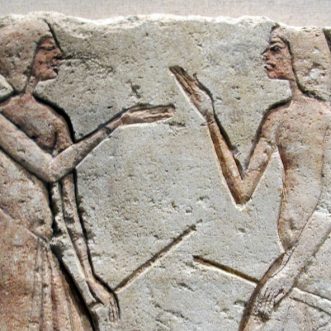

Except when we are in conversation with other humans. In conversation, we think, we reflect, we are fully self-conscious. Sometimes for hours on end. You might even say that conversations with other people are where we fully realise ourselves.

And of course, you can’t have a proper conversation without being fully conscious of the other participants too.

You can’t be seen until you learn to see. Not even by yourself.