February 15, 2019

“To learn easily is naturally pleasant to all people, and words signify something, so whatever words create knowledge in us are the pleasantest. Metaphor most brings about learning.” ~Aristotle

When Blue Rocket Accounting and I started working together, they had a different, very traditional name, based on the surnames of the founding partners. Julie, the new owner, was fascinated by the NASA space programmes, and had already adopted some graphics reflecting that into the branding for the business.

As a result, when we put together the Promise of Value for the business, a powerful metaphor emerged: “we are Houston to your space mission.”

We ran with this metaphor, packaging services up to suit different types of space mission – “Blast Off”, “Maintain Orbit”, “Expand Orbit”, “Reach for the Stars”.

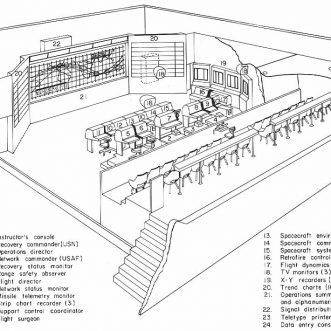

Then we took it further, defining Roles inside the business that are based on key Roles in Mission Control.

So for example, Blue Rocket has a ‘Capsule Communicator’, the primary communication channel for each client mission. Where most accountants would have a ‘Client Account Manager’, Blue Rocket has a ‘Flight Dynamics Officer’ whose job it is to give the client the information they need, when they need it, to keep them on the trajectory they’ve chosen.

This is carried through into the names of key processes: “Deliver Blast-Off”, “Deliver Maintain Orbit”, and so on.

This has proven to be extremely powerful in driving growth.

Firstly, prospective clients find it very easy to grasp exactly what Blue Rocket can do for them, and which package they need, so it makes it easy for them to buy. It’s not for everyone of course, some potential clients find the whole thing too frivolous, but they aren’t the companies Blue Rocket wants to work with, so that’s OK for everyone.

Secondly, its hard to forget why you do what you do when your job title is ‘Flight Dynamics Officer’ or ‘Capsule Communicator’ or ‘Voice of Mission Control’. You’re literally playing out the company’s promise to customers.

So, what would your metaphor be?