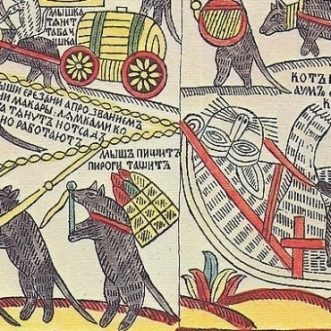

While the cat’s away…

…the mice will continue with whatever processes are in place.

Do you want them to be yours or theirs?

…the mice will continue with whatever processes are in place.

Do you want them to be yours or theirs?

I used to wonder how potters could charge so much for their pots, until I took up pottery.

Then I saw how much work went into producing a pot fit to sell. Not just the work of potting, but also how many pots get thrown away because they broke or cracked in the kiln, or because the glaze didn’t work. Or even because the idea itself just wasn’t good enough. I wondered then how they could charge so little.

A brilliant way to help your prospects and clients understand the value you bring is to show your work. To share the process by which you create that value.

It’s easier when that process is clearly, genuinely focused on them.

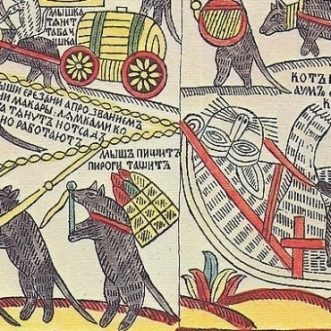

Acumen: Sharpness. The ability to get right to the point, to the heart of the matter.

Acumen is something Jaqueline Novogratz obviously has in spades, because she realises that the people at the bottom of the pile have it too.

And that the best way them to help them is to enable them to apply it to help themselves.

Bottom up, ripple out. That’s the way to do it.

No need for you to be there.

In a business, striking the right balance between control and freedom is hard.

We want the serendipity that freedom brings. To be open to emergent behaviour or trends. And increasingly, we want our workplaces to be human, places where people can exercise their natural powers of creativity, collaboration and problem solving to the benefit of the customer and the company.

But emergence without direction or foundation simply turns into entropy.

The answer is to make sure the culture doesn’t only live inside people’s heads.

Document your Promise of Value as a compass to guide everyone on your journey.

Install a floor through which nobody can fall.

Capture the high-level process as the clue that will get everyone (especially newbies) through the labyrinth safely.

Then set your people free.

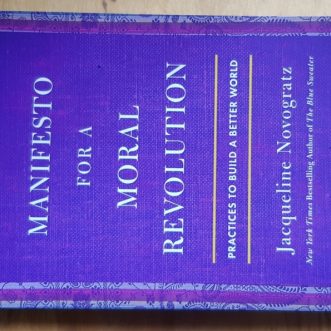

For Adam Smith the pin factory, with its production line and strict division of labour, was the epitome of efficiency. It meant that thousands more pins could be manufactured, which in turn meant more people could afford to own them.

Until eventually a pin became the epitome of worthlessness, a thing you wouldn’t bother to pick up if you dropped it. The factory model solved a production problem.

Products aren’t the only thing we make through our work. We also make people. And since Adam Smith, we’ve also known that the pin-factory approach makes unhappy people.

Humanity no longer needs to be efficient. We no longer have a production problem.

We have a distribution problem. We have an unhappiness problem. And we have a survival problem.

It’s time then, to look for a different mode of production.

One where the survival of our species is the side-effect of work that produces lives well lived for all.

We can start from the bottom up, as we grow our own small businesses:

Think orchestra, not pin-factory.

We had some unexpected guests yesterday. The first I knew of it was the sound.

‘What on earth is that noise?’

I looked up from cleaning the floor, and there they were, a mass of bees madly buzzing across 3 neighbouring gardens. 15 minutes later, they were clumped together near the top of our hawthorn tree.

I looked up my nearest beekeeper on the British Beekeepers Association website, (try them before you call pest control, beekeepers will give bees a good home), and Andrew came over.

We agreed that it was too dangerous for him to try and collect the bees from the tree, so he set up a bait box, to entice them down.

While we waited over a cup of tea, he taught me a bit about bees.

A hive swarms in stages. First the queen leaves, taking half the bees with her, to set up a new colony somewhere. 10 days later, her brood of queens start to hatch, along with the other eggs she’s laid.

It used to be thought that the first queen out killed the others, but research has found that isn’t the case. As each new queen hatches they replicate the original queen’s behaviour – taking off with half the hive. Only each time the half is smaller, even though the hive grows each day as new bees hatch. So each ‘cast’ becomes progressively smaller until the last is about tennis ball sized, and will be lucky to form a viable colony that can get through the following winter.

This it makes perfect sense. The bees are all the old queen’s children. Why kill other queens when you only need half the available resources? There is no scarcity, and so no competition for them. And why kill queens when replicating a simple process maximises the chances that the colony will survive and spread?

We humans could learn a bit from bees.

PS, they’re still in our tree. If they don’t fancy the bait box, they’ll swarm again and find a new place. If you see them, remember to give them 15 minutes to settle down, then call your local beekeeper.

A system of any kind survives through feedback. What feels/sounds/smells/tastes/looks right. Or wrong. Or not particularly either way. Feedback helps us to learn, evolve and interact safely with the world around us. That means that getting good quality feedback about what’s actually going on is crucial. In fact, much of what concerns us as business owners is how to gather feedback effectively and act on it appropriately.

Marketing isn’t feedback. Although you can use it that way. I don’t wear fashion, but I do like to know ‘what’s going on’. A twice-yearly trawl through marketing materials – magazines, shop windows, a look at what’s around and at what people are actually wearing – keeps me up to date.

Social media isn’t feedback. It’s marketing. Increasingly it’s geared to tell us what we want to hear, to entrench us in our worldviews, intensify our outrage, because that keeps us on the platform, there to see the marketing that pays for it.

‘The news’ as we mostly know it isn’t really feedback either. It’s also marketing. Designed to sell a newspaper or a news channel, or a worldview. And it gets more like social media every day.

When Adam Smith wrote “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.”, he wasn’t thinking of JBS S.A, or Anheuser-Busch InBev, or Grupo Bimbo, S.A.B. de C.V..

He was thinking of Mr Jameson, Mr Paterson and Mr McDermid – people his mother knew and spoke to regularly, trying to make a decent living. Who knew that if they tried to short-change customers or cheat their suppliers they’d be found out, word would spread and business would be lost.

But as Adam Smith also wrote “The interest of the dealers, however, in any particular branch of trade or manufactures, is always in some respects different from, and even opposite to, that of the public. To widen the market and to narrow the competition, is always the interest of the dealers. Monopoly of one kind or another, indeed, seems to be the sole engine of the mercantile system.“

There’s a reason marketeers talk about ‘brands’. Brands aren’t people, or even companies, they’re more often monopolies masquerading as humans.

As consumers (and human beings) we should at least keep ourselves aware of that.

The invisible hand can’t work without a market.

The last year or so has forced us all to improvise.

Faced with extreme uncertainty, this is a rational response. Improvisation enables us to quickly learn what works and what doesn’t in a rapidly shifting world. It helps us to try new things, change direction, discover new opportunities.

In effect, the last year turned us all back into new businesses.

If your new new business was able to improvise its way into growth, now might be a good time to pause, take stock and reconfigure it into something more intentional. Make the experiment that paid off repeatable and scaleable. So you can carry on growing on purpose.

Remember to leave some room for improvisation though – it’s how you’ll see the next challenge coming.

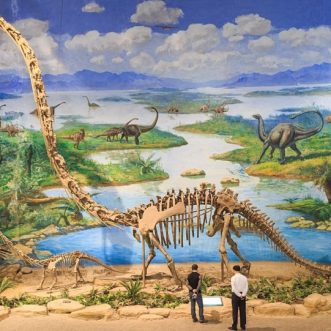

Dinosaurs were at the top of Earth’s food chains for around 180 million years.

They died out because they were unable to adapt through evolution to changes in their environments – first rapid climate change caused by volcanic activity, then of course the famous meteorite.

Homo Sapiens has only been around about half a million years. We’ve arrived at the top of Earth’s food chains by making the Earth adapt to us, driven by models of the world that we make up. Models that turn out to be at best only partly true and often are disastrously misleading.

Will we be the first species to go extinct, not because we can’t adapt, but because we won’t? Because we refuse to change our minds?

That might just make us the stupidest blip in Earth’s history.