Creating bandwidth

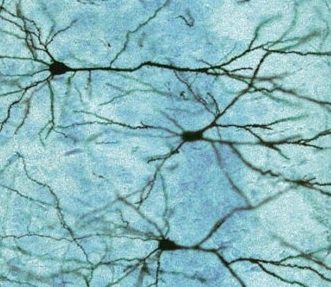

Apparently human neurons are strikingly different from those of other mammals. Neurons are the building blocks of our nervous system – our internal communiactions system by which we percieve and react to the world.

All neurons communicate with each other and with other cells through electrical impulses, produced by ‘ion channels’. In general, the larger the neuron, the more ion channels it has. Until we get to humans.

Our neurons have far fewer ion channels than expected. We still need ion channels, but somehow we are able to get by perfectly well with less of them.

The hypothesis is that by evolving a ‘lean’ neuron model, human brains became more efficient, able to spend less energy on the basics, freeing some up to spend on more interesting things that other mammals don’t do, such as imagining.

That makes sense. The less communication you have to do to support the usual, the more bandwidth you leave to deal with the unusual. Or to imagine a new usual.

Our businesses could learn something from our neurons.