Morrissey

Yesterday, my husband was working his way through his record collection.

As always, Morrissey stood out:

“I am human and I need to be loved – just like anybody else does.”

Something worth remembering as we build our business processes.

Yesterday, my husband was working his way through his record collection.

As always, Morrissey stood out:

“I am human and I need to be loved – just like anybody else does.”

Something worth remembering as we build our business processes.

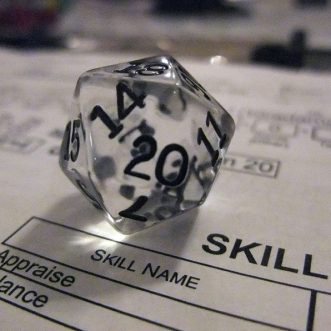

Why do we enjoy playing Dungeons and Dragons?

Because we know the rules. We know the world we’re operating in. We know our own capabilities. We know there is randomness, provided by the dice. And we know that the people we’re playing with know all that too.

Within that framework, each one of us can play freely with the skills we’re given and the attributes we acquire. We can collaborate, go it alone, or switch between the two. If we’re Dungeon Master, we can even change the rules.

Nothing is predetermined, there’s room for the unexpected, yet everything is coherent. It’s a safe space enclosing the perfect balance between constraint and freedom, between box and creativity, between process and play, between community and individual.

Life can’t be like this.

But work can.

Discipline makes Daring possible.

Seth wrote a very interesting blog this week on Monarchists.

“As Sahlins and Graeber outline in their extraordinary (and dense) book on Kings, there’s often a pattern in the nature of monarchs. Royalty doesn’t have to play by the same cultural rules, and often ‘comes from away.’ Having someone from a different place and background allows the population to let themselves off the hook when it comes to creating the future.”

I agree, but I think the whole thing is more subtle and interesting than that.

Kings ‘from away’ could act in ways that were totally unacceptable to the native population – in order to create change. Sometimes, they were even asked in.

Beyond that though, those same Kings were contained and constrained into a purely formal role. They became figureheads, cherished, personally pampered but essentially powerless over the society they ‘ruled’. They didn’t administer the results of their change and they certainly didn’t take over resources. The original population carried on as custodians of the land, society and cuture, as before.

That was the point.

A stranger king enabled a system based on shared authority and collective, consensual decision making to radically change without breaking itself apart. You could almost call them a scapegoat rather than a king. Nowadays we’d call them a consultant.

The challenge then, is not merely to be prepared to ‘put yourself on the hook’ to lead change that will make the community uncomfortable, but also to forgive those of your peers who do it for you.

A system of any kind survives through feedback. What feels/sounds/smells/tastes/looks right. Or wrong. Or not particularly either way. Feedback helps us to learn, evolve and interact safely with the world around us. That means that getting good quality feedback about what’s actually going on is crucial. In fact, much of what concerns us as business owners is how to gather feedback effectively and act on it appropriately.

Marketing isn’t feedback. Although you can use it that way. I don’t wear fashion, but I do like to know ‘what’s going on’. A twice-yearly trawl through marketing materials – magazines, shop windows, a look at what’s around and at what people are actually wearing – keeps me up to date.

Social media isn’t feedback. It’s marketing. Increasingly it’s geared to tell us what we want to hear, to entrench us in our worldviews, intensify our outrage, because that keeps us on the platform, there to see the marketing that pays for it.

‘The news’ as we mostly know it isn’t really feedback either. It’s also marketing. Designed to sell a newspaper or a news channel, or a worldview. And it gets more like social media every day.

When Adam Smith wrote “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.”, he wasn’t thinking of JBS S.A, or Anheuser-Busch InBev, or Grupo Bimbo, S.A.B. de C.V..

He was thinking of Mr Jameson, Mr Paterson and Mr McDermid – people his mother knew and spoke to regularly, trying to make a decent living. Who knew that if they tried to short-change customers or cheat their suppliers they’d be found out, word would spread and business would be lost.

But as Adam Smith also wrote “The interest of the dealers, however, in any particular branch of trade or manufactures, is always in some respects different from, and even opposite to, that of the public. To widen the market and to narrow the competition, is always the interest of the dealers. Monopoly of one kind or another, indeed, seems to be the sole engine of the mercantile system.“

There’s a reason marketeers talk about ‘brands’. Brands aren’t people, or even companies, they’re more often monopolies masquerading as humans.

As consumers (and human beings) we should at least keep ourselves aware of that.

The invisible hand can’t work without a market.

When we put our minds to it, we humans can be pretty brilliant.

Yesterday, I heard about porous molecular cages for the first time. These cages are made up individual molecules that have been designed to imprison another type of molecule – effectively creating a molecular sieve for separating chemicals. As if that wasn’t brilliant enough, the team at Imperial College have been using machine learning and evolutionary models to screen potential molecules for stability, ease of production and scalability.

Also yesterday, I saw a 10-year old Palestinian girl describing how she had grown up amid constant bombings. “Why are you doing this to us?” she asked, “How are we supposed to fix it?”

When we refuse to put our minds to it, we humans can be pretty dumb.

Let’s at least try.

A good process is like a favourite tool.

You know the kind of thing I mean – that ladle you reach for first because it feels right, holds plenty, pours without dripping and washes up easily. Or that favourite saw, that is somehow just easier to work with, even though it’s old and a bit battered.

Often, what makes a good tool work brilliantly is exactly what makes it beautiful. It’s obvious what it’s for, and how it should be used. It’s comfortable to work with, easy to maintain.

Good tool designs are timeless, yet it’s often clear that an individual has crafted them and/or worked with them. They allow for a little personal finessing.

A good tool, like a good process, is one you’re happy to use every day.

It’s one you’re willing to keep in good order, so you can have it to hand always. It’s a tool you’re proud to share, and proud to pass on when your work is done.

Good processes, like good tools, don’t make work, they enhance it.

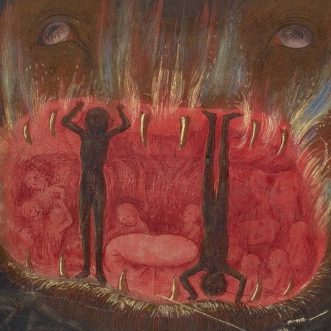

There’s a monster in the office, and everyone’s afraid.

Everyone calls it ‘the Boss’.

The owner thinks it has many heads, eating the business out of house and home, and just not caring enough what they do and how they do it.

The team thinks they know exactly who it is – the control-freak micro-manager, constantly interfering, trying to do everyone’s job and never happy with the results.

Neither are right.

Every business owner I’ve met has a vision in their head for how their business makes promises to clients and keeps them. But there’s often a massive gap between that vision and what they’ve actually managed to communicate to the people whose help they need to achieve it.

That gap is the real monster.

Fortunately like most monsters, it disappears with daylight.

My grandmother was obsessed with spotlessness, which meant my mother grew up under an extreme housekeeping regime: shoes had to be taken off at the door; books weren’t allowed to be seen (too untidy); everything, from picture rail to chair rail had to be dusted every day. And of course at that time, as the only girl of three children, it was my mother’s job to do it.

When she had a family of her own (7 children), my mother had to come to an accommodation with housework. It was pointless spending all day dusting chair rails, when a horde arrived back every afternoon bearing a new cloud of dirt, but to leave it to a once a week blitz would mean living in what felt like squalor to her (and ruin a precious weekend day).

So every day, once we were out at school, she’d spend an hour on housework, using a weekly rota to keep on top of everything. That freed up the rest of her day to read, see friends, shop, whatever, knowing that if a visitor dropped by the house would be, if not spotless, respectable.

The thing that makes housework depressing (if you let it) is that it is never ‘done’. It’s a continuous process. For my mother, the answer wasn’t to avoid it, or even to outsource it. It was to embrace it as a process, enjoy it as part of life, without letting it take over. She knew her house would never be perfect, she preferred to enjoy living in it.

That’s an approach worth learning from.

After all, everything we do (and are) is a process. We’re never ‘done’.

So instead of fretting about a stasis that’s impossible to achieve, let’s make sure we all enjoy doing what might get us there.

Contrary to the popular image, the Amish are not backward-looking. Nor are they against new technology. What they are against is a rush to embrace the new without considering how it might impact on their ethos and their way of life.

Once they have considered, communally, they often adapt a new technology to suit their needs. An iron or a lamp becomes battery- or propane-powered, to preserve their separateness from the outside world. A phone and internet connection is housed in a shared booth at a walkable distance from homes, to maintain the primacy of face-to-face communication and neighbourliness.

The resulting ‘contraptions’ might look odd to us, but the approach is one worth adopting.

Before you jump on the latest bandwagon, ask yourself:

If the technology can’t adapt to suit you, it probably isn’t fit for your purposes.