January 6, 2021

I was trying to think of another example as good as Katerina’s for how to look at something and turn it into a repeatable pattern – a process if you like. This is one I remembered:

Many years ago I was in Italy, having hitch-hiked there with a boyfriend. We wanted to go to Pisa, by bus. One of the frustrating things about being a foreigner anywhere is the knowledge that’s so taken for granted that it remains completely hidden. If you know it, you know it. If you don’t – hard luck.

In this case, frustratingly, we couldn’t work out how to buy a bus ticket. Remember, this was a very long time ago, so there was no ‘online’. In the UK, you could buy a ticket from the driver. Not here. If you didn’t have a ticket, you couldn’t get on the bus. There were no ticket machines we could find – at bus stops, the railway station, anywhere. Where did people get a ticket from? We couldn’t even ask, because neither of us spoke Italian, and we hadn’t thought of bringing a phrase book.

I did speak Spanish and French though, so many nouns were sort of familiar, plus I’d already started to spot a pattern of how words changed between Spanish and Italian. For example, ‘-ado’ in Spanish becomes ‘-ato’ in Italian. So the English ‘passed’ was ‘pasado’/’pasada’) in Spanish, and ‘passato’/’passata’ in Italian. I’d worked out from the notice on the bus that you needed a ticket (‘biglietto’ c.f. Spanish ‘billete’, French ‘billet’). So far so good. But how to work out how to ask where to buy it?

I could read the similarities easier than I could hear them. So I looked at advertising posters, shop signs, notices. I worked out that Italian frequently uses a reflexive sentence pattern in much the same way as Spanish, so that a sentence like ‘Where can I buy a bus ticket?’ could become ‘Where does a bus ticket get itself bought?’.

All I needed now was the word for ‘buy’. I hit lucky with the ad on the side of a building – which contained the line ‘XXX gets itself bought here’

Bingo! (did you know that was Italian?). I could create a new sentence from the pattern I already had

“Dove se acquista un biglietto para el autobus?”

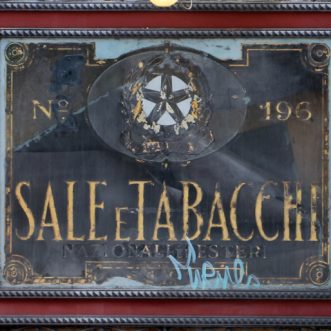

It wasn’t correct – the last bit was pure Spanish. But the person I asked understood exactly what I meant and directed me to the nearest tobacconist. We got our tickets to Pisa, and walked around the outside of the leaning tower at every single level.

I never really learned Italian, but I get by in Italy. Because I recognise patterns from Spanish and French, I can understand what people are saying, and I can construct a sentence that communicates what I mean, even if the details aren’t quite right.

This is no big deal. We all make patterns from the world around us, so we can predict big things and spend more time on the interesting details. It’s just that sometimes you have to do it on purpose. Like when you’re trying to explain a process to someone who’s never done it before.