The product you really make

I’ve saved the best gems from Eric Ries’s podcast episodes with Brian Chesky in Out of the Crisis till last. … Read More “The product you really make”

I’ve saved the best gems from Eric Ries’s podcast episodes with Brian Chesky in Out of the Crisis till last. … Read More “The product you really make”

I’ve written before about multiple stakeholders, so I was pleased to hear what Brian Chesky shared about who he considers to be the stakeholders of Airbnb.

Yes, shareholders. But also employees (who also hold equity), visitors, hosts, suppliers, partners and the communities they operate in.

What particularly struck me was the way Chesky has designed in consideration for each set of stakeholders into the way the business works.

Here are his recommended first steps for setting up in business:

I love this! It means that a business is a system for making and keeping promises – to all its stakeholders.

Sometimes, its impossible to keep all your stakeholders happy, as Airbnb found right at the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis. But it seems that for Airbnb, knowing the promises they’ve pledged to keep has helped them to do the right things, in the right way, as far as they can.

And in the long run, this is what keeps the public wanting you to exist.

*Freeman, R. & Reed, Dl. (1983). Stockholders and Stakeholders: A New Perspective on Corporate Governance. California Management Review. 25. 10.2307/41165018.

We tend to think of keeping things as they are, of doing nothing, staying with the status quo, as the neutral option. But of course that’s not true.

If we don’t act with intention to design our business around what’s important to us, it will still be designed, by everyone in it and the systems surrounding it. Just not on purpose. And not necessarily for the better.

“The system is what the system does.”

I’d rather trust to judgment than to luck.

“Design your company or it will be designed for you.” Brian Chesky, talking to Eric Ries on Out of The Crisis podcast.

It’s easy to talk about ‘a new way of doing things’, a ‘new normal’, but unless we actually make it happen, it’s all too easy to drift back into the old, familiar ways.

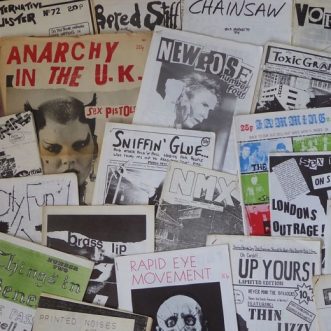

So, here are a few of the people I know of, some of whom I know, who are actually doing a new normal. Showing us that not only is there another way, but that new ways work, often better than the old way:

Some of these people have been doing things their new way for years.

Maybe ‘new’ isn’t so new after all? Not untried, not unsuccessful, just unfamiliar.

People like to do things for themselves.

They also like to have a go at working things out together.

When they can’t, they want someone to be on hand to help.

It seems to me that this is a productive way to think about how to empower people, whether they are clients, users or colleagues:

If you do the first two well, the third will be relatively easy. In fact, you can probably recruit from the people you’re empowering. That’s how the Akimbo Workshops work, and I think it’s at least partly why they work so well.

It’s also how you learn to do the first two better, so don’t be tempted to leave it out.

When we think of ‘process’ we tend to think of production lines. Marvellous arrangements of machines, belts and equipment, where activities like baking a biscuit, or assembling a car, are broken down into the simplest possible steps, so that each step can be reliably repeated with the minimum of variation. At speed, and at volume.

Production lines are fascinating to watch on ‘Inside the Factory’, but are probably less rewarding to work at. Each step is in itself, meaningless, constant repetition makes it tedious.

A production line, whether it’s built in hardware or software, mechanises a complicated process. And once you’ve applied that technology spectacularly well to biscuits, or cars, or mobile phones, it’s tempting to try and apply it everywhere.

But most processes are not complicated, but complex. They involve multiple systems, which interact with each other in unpredictable ways to produce unforeseeable outcomes.

This happens even inside an automated factory. Often the few people you see are not there to perform any of the steps in the process. Their role is to respond to the emergent consequences of several interacting systems, which if left to the mechanicals, would bring the factory grinding to a halt.

All living things are complex systems. Which means that any process involving them is necessarily complex.

It is possible to de-complexify, of course, but only at the expense of de-animating the living. This is why we find factory farming, factory warehousing, factory customer support or even factory schooling disturbing. The only way to incorporate a living system into a production line is to remove its potential for emergent properties – in other words, to kill it.

No wonder people in service industries are wary of ‘process’. They are right to be.

There is a solution though. Which is to recognise the difference between the processes in your business that are complicated and those that are complex and treat them accordingly.

The complicated is amenable to mechanisation and automation. That means it makes sense to automate the complicated wherever you can. Free up your human capacity to deal with the complex, such as interaction with other humans.

The complex can’t and shouldn’t be mechanised or automated. But it is possible to inject some consistency, repeatability and therefore scalability into it, by adopting the analogy of a creative collaboration rather than a production line.

Music, construction, drama, dance, film-making are just some of the complex collaborative, creative endeavours that use a framework, expressed in a shared language, to be more productive, while still allowing scope for the emergent.

The shared language of this kind of process can be idiosyncratic, prompts and reminders rather than instruction, the score more or less sketchy, the film improvised around a premise rather than a script. It can leave room not just for interpretation, but for exploration and experimentation.

That’s the kind of ‘process’ I’m interested in generating. Process that helps us be more human, not less.

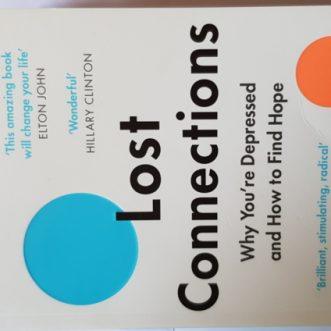

Another read-in-one-go-over-the-weekend book, I recommend. “Lost Connections”, by Johann Hari.

Appropriate for Mental Health Awareness Week and beyond.

This is a book about what happens to human animals when they don’t get what they need from life:

It’s also about ways to put it right.

Luckily, for small business owners, putting it right is not that hard.

We can simply make sure everything we do in our businesses contributes at least something towards these things for the people we work with, the people we work for, and ultimately for ourselves.

It starts by reading this book.

And then maybe this one.

As human beings we are complex sytems, inhabiting complex systems.

Some of these are natural – weather, plate tectonics, ecosystems, the galaxy; some we’ve made up ourselves. And of course, through the social systems we invent, we impact some of the natural ones.

The more we’ve understood our bodies – the physical system we inhabit – the better we’ve been able to cure, contain or prevent individual suffering and maximise the potential for individual flourishing. The more we’ve understood the natural systems we operate in, the better we’ve been able to exploit or enhance them to our benefit.

As businesses we operate within social systems, and if we want to maximise the potential for it’s individual flourishing, it pays to understand those systems better.

They’re both a long read, but with a bank holiday weekend ahead, Capital in the 21st Century and its sequel Capital and Ideology are a great place to start to understand the social system that’s had the biggest impact on everything in our world for the last 250 years.

If reading is not your thing, Capital is available as a documentary film too.

Remember, all models are wrong, so it’s worth exploring as many as you can. Some of them may prove useful.

Many years ago I had a job interview for Booz Allen. Almost the first thing the interviewer said to me was “You’re a bit of a butterfly aren’t you?”

They were wrong. I was just following a normal pattern for someone with my appetite for change.

In work, I’m motivated by evolution rather than stability, and every 3-5 years or so I feel the need to make a big shift. I’m not unusual, that’s how most people like to operate at work.

My interviewer was possibly in a different camp. I asked them how long they’d been with Booz Allen. “20 years.” Clearly in the ‘I like things to stay the same over a long period of time’ preference. Or perhaps their motivational kicks came from working with an international consultancy firm – if the job involves the required level of variety, there’s no need to switch jobs to get it.

I’ve also met people at the other extreme, who are motivated by constant change and uncertainty, and who will pivot almost every year.

The point here is that even without a crisis, it’s worth understanding your own and other people’s appetite for change. People will be de-motivated, under-perform and eventually leave if they aren’t getting what they need from the job they are in.

In a time of crisis and uncertainty this is even more important. A few will thrive on it. Most will find it uncomfortable, unsettling, but bearable. A few will find it almost intolerable.

Bear this in mind as you shake down to remote working. Of course the priority is to get things working and keep going. But if this situation lasts, or you decide to change your way of working altogether it’s worth adjust things in line with these preferences.

It may well be that moving people into different roles will help them and you get through it better.

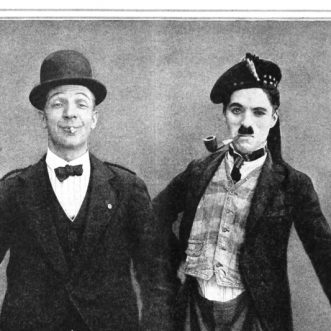

PS the man swapping hats with Charlie Chaplin is Harry Lauder, a music hall (variety) star in his day, and according to Gibbs family tradition, a relation of ours.

I’m fascinated by the way people differ in their ‘working style’ – how they like to operate at work. One … Read More “Going with the grain”