Why justice must be blind.

I’m about halfway through John Rawls’ A Theory of Justice. We’ve finally got to a statement of principles. Which can be informally summed up as something like this:

“All social primary goods – liberty and opportunity, income and wealth, and the bases of self-respect – are to be distributed equally unless an unequal distribution of any or all of these goods is to the advantage of the least favoured.”

That seems pretty obvious. Why has it taken 300 pages to get to here?

Because imagining a just system is a process.

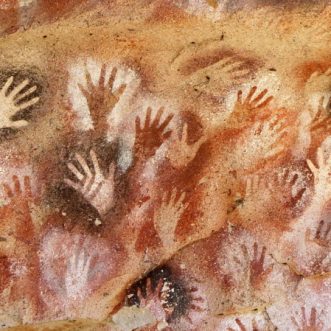

We don’t choose where or when we’re born. We don’t choose our parents or our society or our status in that society. We don’t choose the talents or abilities we’re born with – any more than we choose our eye colour or complement of limbs. That’s all down to chance.

That doesn’t mean we have to accept what we’ve landed in. We can imagine a different kind of setup.

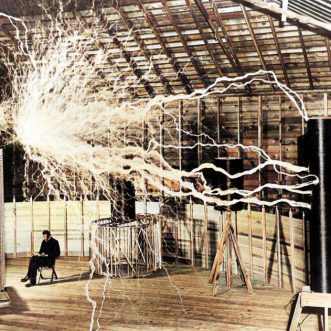

But to do that justly, and end up with something fair, we need a starting point that takes chance out of it. We have to take ourselves out of space and time, and imagine what we as individuals would accept if we didn’t know where we end up in the particular set-up we happen to be born in. We have to make ourselves blind, and build our picture of a just system from there.

That takes a lot of thought and empathy with all our possible selves.

It’s worth the effort, because then we can start to shape our societies to move ever closer to that ideal. Starting with what’s closest to us, our families and our businesses.