Effort

I saw a great demonstration years ago, which is quite fun to try for yourself.

One of your team sits in a chair, facing away from the rest of the team. Somewhere behind the chair, between it and the rest of the team, place a waste-paper bin.

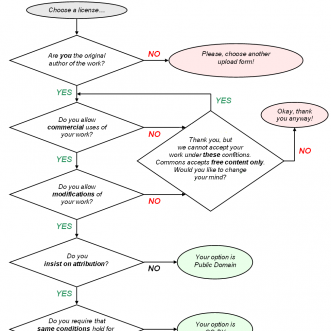

The aim of the exercise is for the person in the chair to get a ball into the waste-paper bin without looking at the bin. They try first on their own. Then they try again.

This time, the team gives them feedback on how they did. First of all, the feedback is just “You missed”.

But after a couple of goes, the team get the hang of it and start giving more helpful feedback – “Too far right”, “About a foot short” etc. This gives the person in the chair information they can actually use to adjust the only thing they can control – how the ball leaves their hand.

The next thing you know, the ball lands in the waste paper bin.

Effort, with feedback, is what actually gets results.

So if you want to improve results, it makes sense to improve the effort that goes into them. And to do that you need to know where you can make adjustments, and get the right kind of feedback on any adjustments you make.

“You missed.” doesn’t cut it.

Thanks to Graham Williams for the memorable demonstration.