Avoiding Bureaucracy

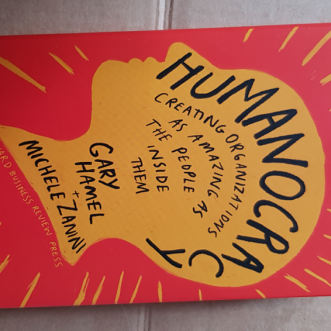

For Gary Hamel and Michele Zanini the opposite of ‘humanocracy’ is ‘bureaucracy’:

“In a bureaucracy, human beings are instruments, employed by an organization to create products and services. In a humanocracy, the organization is the instrument – it’s the vehicle human beings use to better their lives and the lives of those they serve.”

Here’s a quote from Dee Hock that I think, sums up nicely how we get to ‘bureaucracy’:

“We grow to detest any societal organization in which we have no secure place and can find no meaningful life. We ignore it when we can, circumvent it when we must, destroy it if we are able. An organization that does not provide a secure, equitable, meaningful place for each person of which it is composed is not civilised at all; it is to a greater or lesser degree, tyrannical and barbaric.”

In truth, all organisations are instruments, consciously or unconsciously wielded. As Eric Reis observed to Airbnb’s Brian Chesky:

“The product you make is not your website, it’s not the travel, its not even the delightful experiences, the product is the organisation that brings stakeholders together to produce those outcomes.”

The questions to ask are:

- Whose lives are you bettering?

- At what cost to the rest of the world?

It seems to me, that if we want to build a truly successful enterprise that will carry on without us, we should maximise the answer to the first, and minimse the answer to the second.

Fortunately, we’ve invented several ways to do that. One of which is mine.