Rules

How far can you take the idea of a guitar, and still end up with something recognisable as a guitar? … Read More “Rules”

How far can you take the idea of a guitar, and still end up with something recognisable as a guitar? … Read More “Rules”

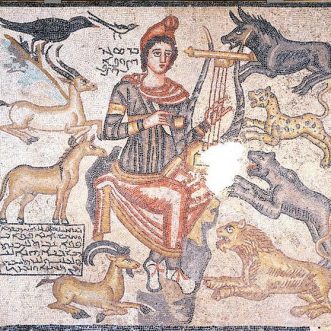

Orpheus is an orchestra without a conductor.

That doesn’t mean they are directionless, they have a score that tells them what to play.

That doesn’t mean they are mechanical, a core group guides the interpretation for every piece they play, and that core group changes every time.

That doesn’t mean they are homogenous, many players dip in and out, although a minimum number of experienced players ensure the Orpheus promise is kept for every performance.

Being conductorless doesn’t mean they are leaderless, it means everyone has to step up and take their turn at leading.

There’s always another way of succeeding. It just needs to be thought through.

Orpheus (the orchestra) has been doing this for more than 40 years.

A complex evolving system, such as a planet, an ecosystem or a business, learns through feedback. That means at least … Read More “Feedback”

Exceptions are where it pays to treat everyone the same. By which of course I don’t mean “computer says no”.

Much better to have a ‘golden rule’ to fall back on that enables anyone on your team to deal with the unexpected in a way that shows you absolutely stand by the promise that you make – even if the exception in question isn’t actually a customer.

Standardisation enables brilliant exception-handling, because it takes care of the routine and so frees people up to be human.

Handling exceptions brilliantly, as a human being, creates fans.

‘Standardisation’ often results in every customer being treated the same – whether they like it or not.

To my mind, a better way of looking at standardisation is that it is about treating the same kind of customer in the same kind of way – and of course, in a way that delivers on the promise you’ve made to them before they bought..

So if, for example, you have 4 different services, you could design 4 delivery processes. They may have a lot of activities in common, but by designing a process for each service, you’re making sure the process is easier for everyone to follow – neither you nor your customer is being made to do unnecessary work.

It may even be the case that different people on your team prefer delivering one kind of service to another, so splitting them means you can always have the best person for the job.

Of course there will always be exceptions, so room has to be left for these to be handled in a way that still delivers on the promise, but they should really be exceptions.

The key to all of this, is to start from the customer’s shoes.

The interesting thing is that, in my experience, getting it right from the customer’s perspective, actually makes things much easier and more profitable to run.

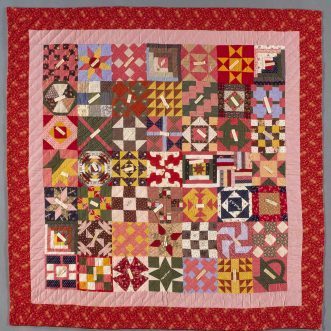

No matter how beautiful the fabrics, or how exquisitely they are cut, they don’t become the end product until they’ve been joined together by a unifying framework.

In this case, its one with considerable give in it.

Quilts have often been made collaboratively, especially in America, where the idea of making a quilt in components (called blocks) really took off. This method meant a quilt top could be assembled very quickly, since the production of blocks was effectively parallelised. If you wanted a bigger quilt, you simply enlisted more friends.

Once the component blocks were completed, they were sewn together to make the top, which was then tacked together with the filling and backing layers. Then everyone got together again to quilt the 3 layers into a single unified whole – the finished quilt.

As well as speeding up the making, this block method allows considerable leeway to the individual contributors. In this Friendship quilt, each contributor has chosen their own block design, but they’ve clearly been given a colour scheme to work with, and at least some fabrics have been shared – its leeway, but not complete freedom.

The result is a bedcover that looks coherent, but is still lively and full of interest. An excellent example of balancing tight rules with interpretive latitude.

Those quiltmakers knew a lot about creative collaboration.

Functional silos are a well-recognised problem in organisational design.

The danger is that separate functions become like fortresses, mini fiefdoms with their own internal rules, reluctant to share information with other silos, poor at ‘passing the baton’ to the next silo when needed, optimising their internal operation at the expense of the whole.

Common solutions involve finding ways to pierce the boundaries between silos – cross-functional teams, rotating people around functions, modelling processes with swim lanes to represent the function responsible.

I think the problem is more fundamental.

Functions are a manifestation of a profoundly internal view of a business. They are about the organisation and the hierarchy, not about the client or customer. They encourage people to forget the Promise the organisation makes and who it makes that Promise to.

So I believe the solution needs to be more radical too.

Instead of trying to build bridges between silos, or tunnel through them, or create elaborate schemes for inter-silo communication, we should simply re-focus the business on clients, and build our organisational framework around making and keeping our Promises to them.

The beauty of this approach is that it makes everything much clearer and simpler for everyone, and its easier to scale.

If your business was a board game? What would it look like? What should it look like?

How do your prospects and customers move through the game?

What routes can they take?

What obstacles do they encounter?

Where are the pitfalls?

Who is there to help them?

What is the prize?

Who wins?

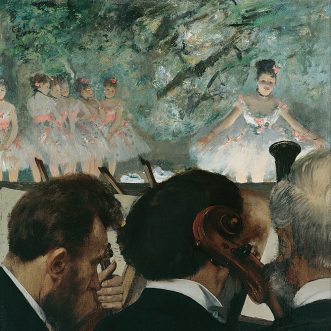

One of the beauties of having a score is that there are no excuses for not playing it.

Playing it and discovering that a particular combination of notes is impossible to produce is fine – as long as you tell the composer. Refusing to play a section because you think it will be too hard, or because you ‘don’t like the look of it’ is not.

A musician wouldn’t expect to be paid, or to stay in an orchestra for long if they persisted in behaving like this.

Why should anyone else?

Of course this works both ways. Every musician that contributes to produce an experience audiences pay for, should share in the profits as well as the applause.