The spaces in between

No matter how beautiful the fabrics, or how exquisitely they are cut, they don’t become the end product until they’ve been joined together by a unifying framework.

In this case, its one with considerable give in it.

No matter how beautiful the fabrics, or how exquisitely they are cut, they don’t become the end product until they’ve been joined together by a unifying framework.

In this case, its one with considerable give in it.

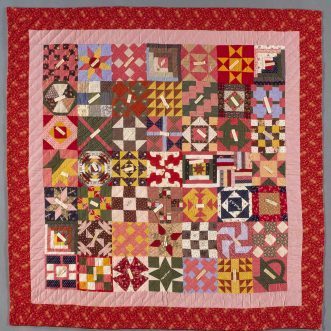

Quilts have often been made collaboratively, especially in America, where the idea of making a quilt in components (called blocks) really took off. This method meant a quilt top could be assembled very quickly, since the production of blocks was effectively parallelised. If you wanted a bigger quilt, you simply enlisted more friends.

Once the component blocks were completed, they were sewn together to make the top, which was then tacked together with the filling and backing layers. Then everyone got together again to quilt the 3 layers into a single unified whole – the finished quilt.

As well as speeding up the making, this block method allows considerable leeway to the individual contributors. In this Friendship quilt, each contributor has chosen their own block design, but they’ve clearly been given a colour scheme to work with, and at least some fabrics have been shared – its leeway, but not complete freedom.

The result is a bedcover that looks coherent, but is still lively and full of interest. An excellent example of balancing tight rules with interpretive latitude.

Those quiltmakers knew a lot about creative collaboration.

“To learn easily is naturally pleasant to all people, and words signify something, so whatever words create knowledge in us are the pleasantest. Metaphor most brings about learning.” ~Aristotle

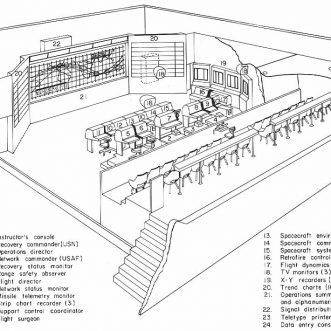

When Blue Rocket Accounting and I started working together, they had a different, very traditional name, based on the surnames of the founding partners. Julie, the new owner, was fascinated by the NASA space programmes, and had already adopted some graphics reflecting that into the branding for the business.

As a result, when we put together the Promise of Value for the business, a powerful metaphor emerged: “we are Houston to your space mission.”

We ran with this metaphor, packaging services up to suit different types of space mission – “Blast Off”, “Maintain Orbit”, “Expand Orbit”, “Reach for the Stars”.

Then we took it further, defining Roles inside the business that are based on key Roles in Mission Control.

So for example, Blue Rocket has a ‘Capsule Communicator’, the primary communication channel for each client mission. Where most accountants would have a ‘Client Account Manager’, Blue Rocket has a ‘Flight Dynamics Officer’ whose job it is to give the client the information they need, when they need it, to keep them on the trajectory they’ve chosen.

This is carried through into the names of key processes: “Deliver Blast-Off”, “Deliver Maintain Orbit”, and so on.

This has proven to be extremely powerful in driving growth.

Firstly, prospective clients find it very easy to grasp exactly what Blue Rocket can do for them, and which package they need, so it makes it easy for them to buy. It’s not for everyone of course, some potential clients find the whole thing too frivolous, but they aren’t the companies Blue Rocket wants to work with, so that’s OK for everyone.

Secondly, its hard to forget why you do what you do when your job title is ‘Flight Dynamics Officer’ or ‘Capsule Communicator’ or ‘Voice of Mission Control’. You’re literally playing out the company’s promise to customers.

So, what would your metaphor be?

Functional silos are a well-recognised problem in organisational design.

The danger is that separate functions become like fortresses, mini fiefdoms with their own internal rules, reluctant to share information with other silos, poor at ‘passing the baton’ to the next silo when needed, optimising their internal operation at the expense of the whole.

Common solutions involve finding ways to pierce the boundaries between silos – cross-functional teams, rotating people around functions, modelling processes with swim lanes to represent the function responsible.

I think the problem is more fundamental.

Functions are a manifestation of a profoundly internal view of a business. They are about the organisation and the hierarchy, not about the client or customer. They encourage people to forget the Promise the organisation makes and who it makes that Promise to.

So I believe the solution needs to be more radical too.

Instead of trying to build bridges between silos, or tunnel through them, or create elaborate schemes for inter-silo communication, we should simply re-focus the business on clients, and build our organisational framework around making and keeping our Promises to them.

The beauty of this approach is that it makes everything much clearer and simpler for everyone, and its easier to scale.

Some people used to believe that the Earth is in the centre of a nest of spheres, containing the moon, all the planets and the sun, as well as several layers of heaven.

Others imagined it as a flat disc supported by a turtle, or an elephant.

Still others imagined it simply as a flat disc, with the sky as a pierced dome over the disc, and light from beyond the dome shining through the holes as stars.

Mental models are useful. They help us explain what’s going on and to work out what we should do in response to events. Often we can get by with such models for a long time – even if sometimes we have to bend the observable facts to fit the model we prefer.

A point comes though, where the facts get bent so far as to become ridiculous.

Then we need to adopt a better model.

If your business was a board game? What would it look like? What should it look like?

How do your prospects and customers move through the game?

What routes can they take?

What obstacles do they encounter?

Where are the pitfalls?

Who is there to help them?

What is the prize?

Who wins?

When a resource is expensive, it seems sensible to use it as efficiently as possible. So we batch jobs up for it, making them wait, so the expensive, and therefore scarce resource can be used to the max.

The problem with this approach is that it distorts the process, optimising a single step at the expense of the rest of it.

This distortion often persists long after the resource in question is no longer scarce. So you get GP and hospital waiting rooms; jobcentres and jury rooms, full of people in forced idleness, just so that the ‘scarce resource’ is maximally productive.

What if we designed our processes around the most critically affected role instead?

Things would look very different, and would be much more efficent overall – although the ‘scarce resource’ might feel a little less important.

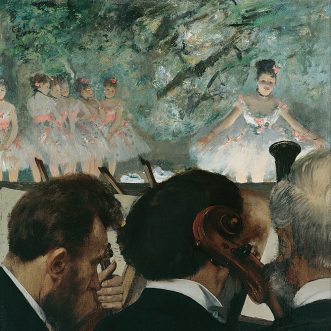

One of the beauties of having a score is that there are no excuses for not playing it.

Playing it and discovering that a particular combination of notes is impossible to produce is fine – as long as you tell the composer. Refusing to play a section because you think it will be too hard, or because you ‘don’t like the look of it’ is not.

A musician wouldn’t expect to be paid, or to stay in an orchestra for long if they persisted in behaving like this.

Why should anyone else?

Of course this works both ways. Every musician that contributes to produce an experience audiences pay for, should share in the profits as well as the applause.

A common reaction to the idea of writing a ‘score’ for a business is “That’s not possible! There are just too many variations we’d have to account for.”

The trick is not to try.

In practice, most of what happens in a business follows, or should follow a ‘usual route’. So we build the score around that ‘usual route’. That keeps it simple and uncluttered, which in turn makes it easy to follow and learn.

Variations usually occur around the technicalities of what the business is doing. They take place at the level of the musician not the score. And as a professional the musician can be safely left to use their judgement to deal with the variation.

As a more concrete example, take dog-walking. Several years ago I worked with a client to franchise their dog-walking business.

We created a ‘usual route‘ for running a dog walk. It covers collecting dogs from their homes and transporting them to the local park, taking them through exercise, training and play in the park, then reversing the process to get them all back home.

All dogs are different. They have personalities and with them preferences about how they come into contact with other dogs. These preferences need to be taken into account at various points in the dog-walking process. It would have been madness to try and include every possible preference and combination of preferences in the main process. So, instead the business owner created a separate ‘Techniques’ handbook, which contained tips and tricks for different situations.

This meant that in the manual, we could simply reference to the appropriate section in the Techniques handbook, together with an instruction along the lines of “Use your knowledge of dog behaviour and your experience of dogs to apply the appropriate technique(s). You’ll find them here ->.”

This created the right balance between dictating the ‘score’ and leaving the musician free to get on with playing it, while at the same time providing helpful hints for variations that might not happen very often.

The result was that everyone was happy. Our first franchisee was delighted: “I know exactly what I have to do.”, and the new franchisor could be confident that her service would continue to delight clients as she grew her business.

We can do this because we’re dealing with human beings, not machines.

Sam at Lewisham Local asked me to elaborate on what I mean by this:

‘scaling successfully is about creating an ecosystem where others can lead’

Here goes…

When you first start a small business you are in control. You make all the promises. You keep them. You are the leader of your own business.

When you can no longer keep up with demand yourself, you add more people. At first, this works, because you are offloading jobs that are easily defined (which could also be outsourced) such as bookkeeping, accounting, diary management, or you are handing over whole areas of responsibility such as sales for example, to another person and simply letting them get on with it.

Beyond a certain size though – perhaps around 5 -7 people – this approach starts to break down. You’ve run out of ‘easy to define’ jobs to offload, and the people you’ve handed responsibility to turn out to have completely different ideas about the promises you are making and how to keep them. They need watching, and controlling.

You are still the only leader, and you spend your time monitoring what other people are doing instead of working on your business. So you get stuck at this scale. You may even decide to scale back at this point, because going further just seems too hard.

What you really want is people who don’t need to be told, who can take responsibility for delivering on behalf of the business, each one of them a leader for the business.

But in order to do this, your people need an ecosystem that supports them.

For me this ecosystem looks like this:

It gives absolute clarity on who the business serves and what the business promises to do for them.

It nails down the values and behaviours that drive ‘the way we do things’ round here, setting expectations for behaviour for everyone in and around the business.

It is structured around processes, not functions, and certainly not management hierarchy. Processes start and end at the boundary of the organisation – they go from end-to-end, following the lifecycle of a prospect through to client and beyond. In this way the ecosystem stays focused on the people it serves. Everything that goes on inside the ecosystem is a side-effect of attracting and serving clients.

Processes provide clear direction on what needs to be done when, both to make the right promises to the right people, and to deliver on those promises – without specifying in excruciating detail how to do those things (although they may reference a library of techniques or ‘how-to’s that beginners may find useful).

Processes set out the usual run of events, without enumerating every possible scenario. This means that technical expertise still resides in the individual, who can exercise their professional judgement to handle exceptions, based on their own knowledge and experience, plus the values and behaviours expected of them.

It is based on roles, not individuals. Roles have clear responsibilities to clients. Roles run processes and each process is the exclusive responsiblility of one role. In effect every role-player leads their own processes. Roles may participate in processes they are not responsible for.

It ensures that everything is visible to everyone, and that all the resources needed to perform a role are available as and when they are needed.

Finally, it includes feedback mechanisms, so that it can improve and evolve. This includes rewards, which to be effective, should fairly reflect individual contributions.

In this ecosystem individuals can play more than one role, and the same role can be performed by many individuals. This is how you scale – you simply add more individuals in the roles you need.

Ideally, an individual runs an entire end-to-end process – effectively becoming a mini-business on their own, a bit like a franchise, but internal. This is how you can scale and transform to an employee-owned, employee-run business.

To begin with, you as the original leader will want to monitor and action all feedback, but roles should see everything too. Their responsibilities include improving the ecosystem based on this feedback.

Over time, as you become more confident that your people are running the business as it should be, you can let them get on with it – they will lead the business instead of you.

It takes a while to build an ecosystem like this, but once you have it, scaling becomes much easier.

That was a long elaboration – thank you for reading it.

Thank you Sam for asking it.