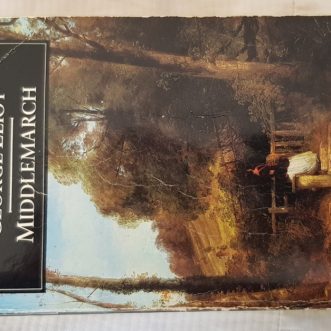

Why I read fiction

Middlemarch is my favourite work of fiction precisely because George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans) succeeds so well in this endeavour.

Not everyone in the book is good, or beautiful, or admirable or likeable, but by the end you feel they are all worthy of the investment of your attention. Even the ‘villains’. You may not approve of everything they do, but you at least understand how they got there. Not through being ‘good’ or ‘evil’, but through being human, by the choices they take at each little fork in the road, how they justify those choices to themselves and how that leads to the route taken at the next fork, and the next.

Reading fiction is one of the most effective ways I know to expand my horizons. I’ve ‘met’ far more people through fiction than I could ever hope to meet in the flesh, from all sorts of backgrounds, times and places. Practising empathy for these characters, written by and about people outside my comfort zone is great practice towards doing it for real.

I know quite a few businesses who keep a library of business books for their team. Perhaps its time to add some fiction.