May 27, 2020

When we think of ‘process’ we tend to think of production lines. Marvellous arrangements of machines, belts and equipment, where activities like baking a biscuit, or assembling a car, are broken down into the simplest possible steps, so that each step can be reliably repeated with the minimum of variation. At speed, and at volume.

Production lines are fascinating to watch on ‘Inside the Factory’, but are probably less rewarding to work at. Each step is in itself, meaningless, constant repetition makes it tedious.

A production line, whether it’s built in hardware or software, mechanises a complicated process. And once you’ve applied that technology spectacularly well to biscuits, or cars, or mobile phones, it’s tempting to try and apply it everywhere.

But most processes are not complicated, but complex. They involve multiple systems, which interact with each other in unpredictable ways to produce unforeseeable outcomes.

This happens even inside an automated factory. Often the few people you see are not there to perform any of the steps in the process. Their role is to respond to the emergent consequences of several interacting systems, which if left to the mechanicals, would bring the factory grinding to a halt.

All living things are complex systems. Which means that any process involving them is necessarily complex.

It is possible to de-complexify, of course, but only at the expense of de-animating the living. This is why we find factory farming, factory warehousing, factory customer support or even factory schooling disturbing. The only way to incorporate a living system into a production line is to remove its potential for emergent properties – in other words, to kill it.

No wonder people in service industries are wary of ‘process’. They are right to be.

There is a solution though. Which is to recognise the difference between the processes in your business that are complicated and those that are complex and treat them accordingly.

The complicated is amenable to mechanisation and automation. That means it makes sense to automate the complicated wherever you can. Free up your human capacity to deal with the complex, such as interaction with other humans.

The complex can’t and shouldn’t be mechanised or automated. But it is possible to inject some consistency, repeatability and therefore scalability into it, by adopting the analogy of a creative collaboration rather than a production line.

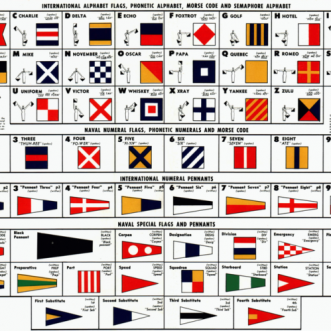

Music, construction, drama, dance, film-making are just some of the complex collaborative, creative endeavours that use a framework, expressed in a shared language, to be more productive, while still allowing scope for the emergent.

The shared language of this kind of process can be idiosyncratic, prompts and reminders rather than instruction, the score more or less sketchy, the film improvised around a premise rather than a script. It can leave room not just for interpretation, but for exploration and experimentation.

That’s the kind of ‘process’ I’m interested in generating. Process that helps us be more human, not less.