Gen Z

Gen Z are demanding what every generation before them has always wanted – #autonomy, #purpose #agency #mastery #community.

Good for them!

Give it to them. And watch your business scale.

Gen Z are demanding what every generation before them has always wanted – #autonomy, #purpose #agency #mastery #community.

Good for them!

Give it to them. And watch your business scale.

At this morning’s Like-Hearted Leaders gathering we had an interesting discussion around what leadership is or could be.

It was an interesting, intricate, circular discussion.

But in the end, I think what leadership could be might be best summed up in the LHL values:

It’s an interesting question though.

What does leadership mean to you?

What does it mean to whoever you lead?

“There’s an interesting rule called the 70-20-10 rule, which states that 70% of learning comes from doing, 20% comes from observing in relationship, and only 10% comes from actual instruction.”

This is from my friend Grace Judson’s leadership newsletter (well worth subscribing to).

Here’s how you might apply it if you have a Customer Experience Score in place:

It’s a good idea to hold regular reviews of the Score, as part of group practice sessions. Over time, people will internalise the Score, but not necessarily as it is written. You want to share desirable variations and eliminate the undesirable ones. Regular group practice will enable this.

It is of course possible to do all this without a Customer Experience Score. It will be harder though, because you have to spend time agreeing whose version of ‘how we do things round here’ is the right one.

I’ve talked before about the application of pin-factory thinking to work that requires empathy, creativity, imagination, judgement and flair. This kind of thinking reduces management to supervision, control, and reporting. Activities that are easily automated, but add little value.

No wonder we have an employee engagement problem, an innovation problem and a productivity problem.

Because we have a management problem.

People don’t need managing. We are perfectly capable of managing ourselves, and do so every day.

We don’t need supervision and reporting. We need communication – a vision, a score to follow, feedback on how we’re doing.

We don’t need to be controlled. We need freedom – to make mistakes, learn from them, correct ourselves, improve how we do things.

We don’t even need to be led. We can lead each other – the right leader, at the right time to deliver what’s required.

Down with management!

Long live responsible autonomy!

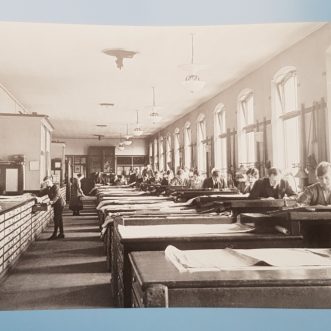

George Stephenson built his steam engines without drawings. He didn’t need them. As both designer and maker, he could keep everything in his head, using rules of thumb, jigs and tools to speed up the making. Every engine was hand-crafted and unique.

His son, Robert Stephenson, set up the first railway drawing office. He separated production from design so that both activities could be scaled. The drawings communicate the design to the people who build.

When we first set up in business, we behave like George Stephenson. We hand-craft each and every user experience. We learn from each iteration what customers really want.

And when we scale, we expect our team to be able to use the rules of thumb, jigs and tools we created along the way. We assume that they have in their heads what we have in ours. So we get frustrated that they don’t do things ‘the way they should be done.‘

That’s unfair. They don’t know what we know, haven’t learned what we learned, didn’t design the jig, tools and rules of thumb we expect them to use, don’t know to get the most from them.

We forget to give them the equivalent of drawings – our design for a customer experience, on paper, for them to deliver.

The good news is that most of us aren’t generating thousands of designs, but a few. Even better, because we’re dealing with human interactions, a certain amount of sketchiness makes things more effective, not less. The best news is that once our initial designs are out there, everyone in the business can improve on them.

Before you share the work, share the design behind it.

P.S. I thoroughly recommend the book this picture came from.

Management – the co-ordination of activities executed by many people – is expensive. Managers don’t contribute directly to the bottom line, and good managers cost good money to hire. So it’s no surprise that firms around the world have been looking for a way to get rid of managers.

One solution is to automate – management by algorithm, as used by Uber, deliveroo and the like, and increasingly applied to fields such as home-care. This is hideously expensive to set up, of course, and it depends on creating an effective monopoly. Plus it effectively turns humans into mindless robots, paid accordingly.

The other solution is to devolve responsibility out and down to the front-line – radical de-centralisation, where teams on the front line manage themselves. An extreme (and very successful) example of this is Haier Industries, essentially what Corporate Rebels call ‘the biggest startup factory in the world’.

At Haier, ‘teams’ are startups, consisting of internal and external people (such as suppliers), all working to create value for customers, sharing the risks and the rewards along the way. They are monitored and supported, but not controlled. Haier doesn’t decide what will work and what won’t, the market does.

In contrast to Uber and the like, Haier has created a highly profitable solution to getting rid of managers – by creating an ecosystem that enables self-managing people to do what only humans can do – create value for other humans – supported and rewarded by systems that help them to keep growing.

In the future, there will be no managers, only management. What kind of management do you want for your business? Uber? or Haier?

I know which I’d prefer.

I learned a new concept this morning: ‘Founder’s syndrome’. Here’s the Wikipedia definition:

The founder responds to increasingly challenging issues by accentuating the above, leading to further difficulties.[29] Anyone who challenges this cycle will be treated as a disruptive influence and will be ignored, ridiculed or removed. The working environment will be increasingly difficult with decreasing trust. The organization becomes increasingly reactive, rather than proactive. Alternatively, the founder or the board may recognize the issue and take effective action.[30]

A lot of this looks to me like the classic painful transition from one-person-band, to few-person-band, to full-blown company. Which is really the transition from a small, personal, human-scaled business to a large, impersonal capitalist corporation. The founder wants to keep things personal and true to their original vision. New owners or new management want to make things efficient, corporate and therefore impersonal. As far as the founder is concerned, they want to make it ‘someone else’s business‘. Of course the founder resists.

There is a preventive for ‘Founder’s syndrome’.

Embed the founding vision and personality into the operating processes of your business before you try to scale, with a Customer Experience Score. You’ll be able to scale without managers, even without investors other than the people you serve. The best of both worlds: personal, true to the original vision and magnifying your impact.

Even better, once it’s built into the way your business works, your Score takes on a life of it’s own, nurtured and improved by everyone in the business. It becomes harder for anyone to interfere – even you.

Letting ‘art’ into a business feels wrong somehow. Surely the point of business is predictability, conformity, delivering to specification? How can you let people ‘do art’ on this without losing these things?

The kind of precision we usually think of when we think about ‘predictability, conformity, delivering to specification’, is really only necessary for manufacturing. Even then, the manufacturing part is only a fraction of what makes up the customer experience.

If art happens in that tense space between rules and license, restriction and freedom, certainty and uncertainty, you can at least control what happens on one side of the space. You can specify ‘the least we should do’, with as much precision as you like. That means there is no downside to the art that can take place, only upside. You can predict that specification will be met at least, perhaps exceeded.

The output of artists constantly evolves, as they explore that space of tension between the rules they’ve set themselves and whatever it is that they wish to express. Each individual work is a specific response to that tension, different from every other, but taken together, the whole body of work is coherent. You can tell it’s all from the same artist.

The thing your business exists to express is your Promise of Value. Everyone in the business is trying to create art in the tense space between your Promise of Value and the floor you’ve defined. Each individual making and keeping of your Promise – or customer experience – is a specific response to that tension, different from each other, but coherent, taken as a whole. You can tell they’re all from the same studio. You can predict that every response will conform to your Promise of Value.

Looked at this way, your job as business owner is not to control individual output, but to define the space – the studio if you like – where your people, your artists, can create output that delights the people you serve.

Why would you do this? Because art commands higher prices than factory-made. People value human.

Of course, inspiration on its own isn’t enough. Inspiration needs a starting point, a constraint, something to bounce off, spark to or rebel against.

The maker of this ‘crazy’ quilt was already constrained by the assortment of odd-shaped leftovers they had. Perhaps also by the limited colours they’d been given. They decided to impose another constraint – the nine square layout. The result isn’t random. Nor is it purely functional. It satisfies more than the need to keep warm at night.

Why would someone do this?

We humans like order as much as we like wildness. We desire both certainty and uncertainty, rules and license. Pulled by these opposites, we find the tension between them uncomfortable.

So we turn it into the most delightful thing of all – art. Capturing a fleeting, but satisfying moment of balance between the two. The ‘right’ balance is elusive, every time we try, the result is different. That’s what keeps artists in practice. The ‘right’ balance is also personal. That’s what gives each artist their own style.

If you want your business to feel human, it needs to be a place where art can happen.

You can’t dictate the artistic solutions. But you can create the required level of tension, by imposing rules, order and constraints.

If those constraints are designed around making and keeping your promise to the people you serve – if they define a floor, but no ceiling – you’ll have created a safe, exciting and human space for everyone.

Especially you.

The problem with a hierarchical management structure, is that it’s expensive – adding layers of overhead and transaction costs that have to be carried by the revenue-generating part of the business. Even worse, it encourages everyone working within it to focus on the wrong thing – their immediate boss. And that makes work miserable for many, especially those at the bottom of the pyramid.

Alternatives to hierarchy, such as holacracy, co-operation and teal address this by delegating much of the management and decision-making to the people at the coal-face – no longer the bottom, but the cutting edge, where the business meets its customers.

This doesn’t reduce overhead that much because in effect, as Dr Julian Birkenshaw of London Business School observes, these structures “replace a vertical bureaucracy with a horizontal one”. Considerable interaction costs remain as people collaborate and generate consent to create emergent actions. But at least the focus is where it matters, on the customer, client or stakeholder.

It seems to me that what’s really needed is both structure and emergence. A structure that takes the thinking out of doing the right thing most of the time, but allows for emergence at the edges to respond to exceptions and to evolve. The main thing is that both the core structure and the processes for emergence are focused on the same thing – the customer, client or stakeholder.

By now, you know all about my core structure:

Even hierachy works better around this. Replace that with holacracy, co-operation, teal or responsible autonomy, and your business will fly.

Discipline makes Daring possible.