Relics

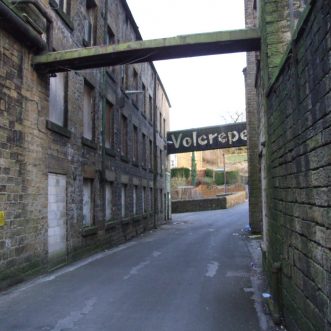

Yesterday, I drove across the Peak District, along the Derwent Valley and up through Glossop to Calderdale.

Almost the whole way, wherever there was a river below, the valley was thick with old mill buildings, built to last. Some famous, like Arkwright’s Cromford and Masson Mills, now world heritage sites. Most forgotten, derelict, or hidden in the core of industrial estates, or turned into housing.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, there were well over 100 cotton mills in this area, their owners rushing to embrace the new business model pioneered by Arkwright – a factory powered by water.

Within 30 years, many of them were out of business. A new technology shift had taken place, from water power to steam, which meant independence from rivers, and freedom from the size constraints imposed by valleys. Small factory owners, unable to justify the investment could no longer compete and went under.

Now of course, very little cotton is spun or woven in the UK. Yet more technology shifts meant that even large factories drifted slowly into obsolescence.

To us now, this is history. But technology is always shifting, increasingly in people-based service industries like accounting, consulting and law.

You can embrace the latest business model, or make a virtue of keeping to the old. The trick is to do it consciously, keeping an eye out for whats next.