Questioning

When you’re stuck, questions can be more helpful than answers.

As I found at Like Hearted Leaders this morning.

Why not give them a try?

When you’re stuck, questions can be more helpful than answers.

As I found at Like Hearted Leaders this morning.

Why not give them a try?

When, as kids, we had scoffed our own sweetie allowance, and wanted more, we’d have a go at appropriating the shares of our younger siblings. This rarely took the form of outright theft. We knew that was wrong. So we’d find other less obvious ways to achieve the same result.

We cajoled, we pleaded, we promised swaps. When that failed we bullied.

My parents called this behaviour ‘greeding’ – manipulating others into giving up their share, so you can have more.

We grew out of it, but it feels like an awful lot of greeding goes on in the grown-up world – beyond the obvious thefts, ponzi schemes and cons.

Banks put small businesses into debt with ‘recovery programmes’, taking over their assets once they’ve gone bankrupt. Firms force individuals to sell their homes for needed healthcare, raid pension funds to pay private equity loans.

Seed companies patent f1 hybrid seeds, forcing small farmers around the world into destitution. Soft drinks manufacturers negotiate first call on local water supplies, leaving ordinary people to pay more for less.

Manufacturers shut their eyes to child labour, slavery, invasion and habitat destruction in their supply-chains.

All so they can build up the means to do more of the same.

It’s called accumulation by dispossession. It’s happened throughout human history, of course. But not everywhere, not all the time. For the last 500 years we’ve relied on a system that can’t work without it.

And that can only end in tears.

Of course, inspiration on its own isn’t enough. Inspiration needs a starting point, a constraint, something to bounce off, spark to or rebel against.

The maker of this ‘crazy’ quilt was already constrained by the assortment of odd-shaped leftovers they had. Perhaps also by the limited colours they’d been given. They decided to impose another constraint – the nine square layout. The result isn’t random. Nor is it purely functional. It satisfies more than the need to keep warm at night.

Why would someone do this?

We humans like order as much as we like wildness. We desire both certainty and uncertainty, rules and license. Pulled by these opposites, we find the tension between them uncomfortable.

So we turn it into the most delightful thing of all – art. Capturing a fleeting, but satisfying moment of balance between the two. The ‘right’ balance is elusive, every time we try, the result is different. That’s what keeps artists in practice. The ‘right’ balance is also personal. That’s what gives each artist their own style.

If you want your business to feel human, it needs to be a place where art can happen.

You can’t dictate the artistic solutions. But you can create the required level of tension, by imposing rules, order and constraints.

If those constraints are designed around making and keeping your promise to the people you serve – if they define a floor, but no ceiling – you’ll have created a safe, exciting and human space for everyone.

Especially you.

Over the long weekend, I had a good rummage through some of my quilting books. It was interesting to come back to them after a gap of a few years as they’ve been in storage while we built the extension.

What struck me going through them now, was just how prescriptive some of the project instructions are – specifying exactly which fabrics to use – down to the manufacturer, designer, range and colourway – exactly how to cut the fabric up to get the required number of pieces, and exactly how to sew them together to make a quilt top. They are instructions for making a replica of a particular quilt.

I don’t know why, but I find this approach quite disturbing. Perhaps because it feels like it isn’t really creative. If I follow the instructions to the letter I’ll get a carbon copy of the quilt in the picture. There’ll be nothing of me in it. There’s no real learning in it either. I learn to follow instructions to replicate a particular quilt, that’s it.

By contrast other books – generally the older ones, are quite freestyle – specifying only ‘light’ or ‘dark’ fabrics together with the number of different shapes needed – assuming that you know how to cut a square or a triangle (or that you’ll refer to the ‘how-to’ section at the beginning of the book). Some even include pictures of different versions of the same patchwork pattern, so you can see how the look changes with different fabrics. These are recipes for making a kind of quilt. Recipes I am encouraged to make my own, right from the beginning. I learn to think about colours and how they work together, I learn how to think about cutting. Most importantly, I learn about my own taste. I learn a process I can apply to different starting materials to generate my own unique results.

For me, the difference between these approaches shows the difference between workflow and process. Workflow turns human beings into mindless replicators. Process frees them to be creative.

Imitation or inspiration. Which would you rather encourage in your team?

Last year, at the start of the pandemic, eight staff at the Anchor House Care Home moved in.

They spent 56 nights on makeshift beds, isolated from their own families, to protect their residents.

The result? Nobody in the home even caught Covid-19.

Anchor House is a small care home, in a lovely old house in Doncaster. The only one owned by it’s parent company Authentic Care Services Ltd. According to the CQC it ‘requires improvement’.

Hmmm.

Perhaps the CQC isn’t designed to measure what really matters.

A boss is someone who tells you what to do. Often they also tell you how to do it. A boss’s job is to get more work out of you than they are paying you for.

On the whole, we don’t like how it feels to be on the receiving end of either of these things, which is why we leave big corporates to become ‘our own boss’.

But when we have to work with other people, we have to become ‘the boss’. And it doesn’t matter how much you dress it up as leadership, the job is the same – getting more work out of others than we’re paying them for, telling them what to do and how. It’s uncomfortable. It feels wrong. Especially when we’re a small team that feels more like family. You don’t do these things to family.

It’s also frustrating, because your team know what a boss is, and what a boss does. and they don’t like it any more than you did.

Turning yourself into the thing you hoped to leave behind is not inevitable. If you build a system that enables every person in your enterprise to lead, and rewards them accordingly, you avoid the discomfort and frustration of being a boss. Ironically, it enables everyone to get more work done too. So if you’re focused on impact rather than profit, this is the way forward.

When everyone’s a leader, the boss can happily disappear.

What do we mean when we call something ‘a commodity’?

It means its substitutable, interchangeable, you’ve seen one you’ve seen them all.

It means we don’t have to think about it. It’s just there. To hand when we need it, otherwise invisible.

I no longer use ‘commodity olive oil’. Mine comes from Marije in Portugal. I’ve seen her family harvesting the olives. I’ve seen the designs for the special ceramic bottles it can come in. I’ve seen the ship ‘Gallant’ sailing to pick her oil up, and sailing back to Penzance to drop it off. I know the names of many of the people involved in making that happen.

And every time I use my oil, which is every day, I think of them and all the work that’s gone into getting olive oil to my table. I feel connected to a network.

My olive oil is not a commodity, I pay well above average price for it, and it’s worth every penny.

Commodification is not inevitable. We can choose to be different, as buyers, producers and middle-men.

As a community.

NASA engineers had noticed a problem with the O-rings used to seal joints in the boosters of the Challenger space shuttle. When the weather was cold at launch time, the O-rings failed to seal the gaps properly. But they couldn’t quantify the effects, so were not allowed to act on their concerns. After all, the NASA engineering watchword was : “In God we trust. All others bring data.”

But what if you don’t have data? Does that mean you just leave it to God?

Of course not.

As Richard Feynman said at the enquiry following the disaster “If you don’t have data, you must use reason.”

Our processes must allow for that.

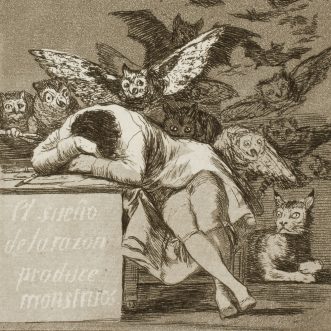

If the sleep of reason produces monsters, imagine what wonders we create when we combine data with waking reason, driven by humanity?

Our processes must be designed for that.

HT to Abishek Chakraborty for the prompt.

I’m not remotely into football, but inevitably I catch the odd England game – or at least snippets of them.

What’s struck even me this time round, has been the aim to win rather than merely not lose. There’s been a definite effort to actively score more goals than their opponents, rather than get away with letting fewer goals in, or relying on penalty shoot-outs.

This is not rocket science. If you try and score goals, while preventing the other side from scoring against you, you give yourself more chances to win, and win conclusively. It also makes for a much more exciting game to watch and to play – for both sides.

Delightful as it is to win, winning isn’t everything. How you win matters. The process matters. And speaks volumes about your priorities.

How do you embed ‘process knowledge’ – the knowledge of how to do things – into other people’s heads across space and/or time?

Well the first step is obviously to get it out of your head first. Then you have to communicate it to others in a way that is easily absorbed yet also ‘sticky’.

One familiar way is through apprenticeship – repeated physical practice under the eye of a master. Great over time, although slow, harder to apply over space.

Another familiar way is to write things down – in manuals, standard operating procedures, process maps. This solves the problem of space as well as time, but is actually notoriously un-‘sticky’. Nobody likes reading manuals – in fact most people hate it.

So the best way is to create some combination of scribing and physical practice that combines the best of these approaches.

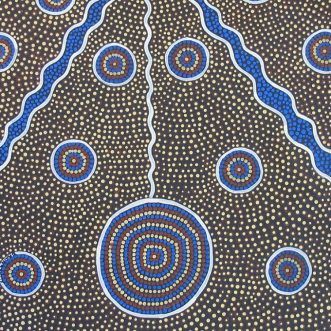

And that’s just what aboriginal Australians have been doing for around 40,000 years. They preserve their culture – their ‘way of doing things’ through a complex combination of activities that includes mapping, painting and sculpture of all kinds, song, dance and actual doing, tied to a landscape that acts as both operating territory and memory jogger.

What’s interesting is how even the ‘scribing’ is so physical and multisensory – maps can be physical representations that are walked around; memorisation takes the form of songs and stories attached to landmarks. Painting or dancing is not just a way of representing an activity, its a form of doing it.

We process mappers and manual writers could learn a lot from this approach.

Hmmm.

Watch this space.